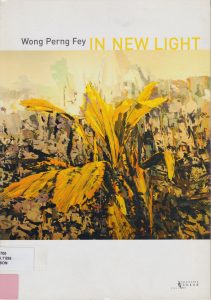

Wong Perng Fey

In New Light

To have a basic love for a country starts from knowing the geography of the country, which is the land, from where everything grow.’

Consummate painter of the Malaysian landscape, Wong Perng Fey, returns to VWFA KL this July for his eighth solo exhibition. In choosing the land as his subject, Perng Fey has always sought for a greater sense of belonging, of identifying with the country. He holds to the belief in and seeks meaning through a subtle measuring of his personal relationship with his subject, the changing nature of how he responds to his surroundings.

This new body of work is marked by Perng Fey’s interest in charting the emotional responses to living in the New Village environment, a place he grew up in, left and eventually returned to. But as he absorbs the legacy of his hometown, Perng Fey’s exploration expands to its surrounding terrain, in both natural and constructed places. More importantly,Perng Fey’s paintings speak of the invisible yet intimate relationship between man and his environment, creating a haunting picture that both celebrates and mourns for the changes that time (as well as development) has wrought upon the land.

Wong Perng Fey: Light Sears. Memory Burns

by Simon Soon

As a painter of the Malaysian landscape, Wong Perng Fey’s vocabulary is ambitious and extensive. From his earlier works that sought to achieve a kind of panoramic vision of a national landscape to the later introspective inquiries into the “landscape” of his memory, the range of his creative responses in seeking for a sense of belonging with his country verges on the romantic.

For the artist, landscape and memory are deeply connected. The land is the lode of Wong Perng Fey’s memories, it is where he stores and enriches them, and finds ways of coming to terms with his past and larger history. Through painting, he distills this into an abstract relationship with a country that is in many ways still unsure and insecure of her identity. Hence his approach has hitherto been reductive, finding an essence to what landscape really means for his young country.

However, this new body of work has shied away from casting out an archetypal or mythic mold to the question of what constitutes the Malaysian landscape. Instead of modeling what is “home”, or “the land” through his paintings, the artist has here abandoned the search for that which is essential or characteristic. In many ways, the new works are much less romantic. They no longer convey the Malaysian landscape as an abstract idea that can be captured in a singular arresting image. In describing his paintings, Perng Fey is quick to point out the locations of his subjects. Whether the paintings are of city views or abandoned shanties, scenery by the roadside or the lake near where he lives, they all refer to a particular time and a place that have captured his attention.

Perng Fey takes frequent drives in the New Village[i] and its surrounding area, exploring both the natural (or what is left of the natural) as well as the built environment, capturing the distinct mood and flavour of a particular scene in a particular site. There is ‘The Young Palm’ which impressed him on one of these drives. He speaks of its monumentality and impact – the frontality of the fronds commands attention to its presence, standing tall against the backdrop of an equally majestic peak, to symbolize both prospect and growth. He sees an equally “organic” force in the rhythm and structure of the city as a concrete jungle. ‘Downtown 80s’ shows a burgeoning cityscape as tendrils creeping along a plotted lattice, rising upwards and onwards. The cost of development is never entirely concealed – the artist takes care to disclose its ramifications, as in ‘Ulu-ulu’, depicting the deserted rough shacks as the ruinous sites of our modern times, brown with neglect, forgotten and abandoned to a slow rueful dilapidation.

In encountering different places and different memories of the past, this series draws these locations into proximity, through a rhythm that suggests that they share no one binding feature. For Perng Fey this discovery has resulted in a conceptual shift: The land is no longer singular; the land is plural. This plurality engenders qualitative differences, not just in subject matter, but also in feelings and experience. By honing in on specific locations, the artist has been able to explore with greater accuracy how memory is linked to the landscape. Yet, this conceptual development has also convinced him to find a new visual language that is able to express succinctly the ambiguities (at once intangible and lucid) of memory.

Having traveled overseas in the past few years, Perng Fey came to observe that the tropical sunlight is much fiercer than its counterpart in countries with temperate climates. The revelation of this contrast and his fascination with it, has led him to work extensively with oranges and yellows, as if to flesh out the luminance and intensity of the lighted surface, accenting the gleaming tropical light as a determinant in how memory is approached and studied.

In ‘Sunset in Pekeliling’, the artist plots the reflection of sunlight on the glass windows of a building. The pictorial field is awash in a burning glow, at times radiating like a mirage. The glow is paint, but it is also the pulsation of light animating and capturing the form and shape of the subject. It can be argued that a number of works in this exhibition form a new exploration into the nature of light in the painting of landscape. Swathes of paint are layered in works such as ‘Towards the Lake’ and ‘Purple Twilight’ in arrangements that respond to different light textures. Elsewhere, in ‘Dreaming of a Tropical Paradise’, the hermetic landscape is almost lost, basking distantly in the glow, luring us into its warm ecstasy.

Light sears. For memory and light are synonymous in Perng Fey’s new paintings. Their qualities are windows beyond the specificity of the subject matter, opening our eyes to memory’s intangible compound – light. The artist seems to suggest that light is that which creates the shapes and images of our memory and that the memorable – our ties and affections towards a particular place – is more than its shape and form. It is a glow, a nervous energy and a feeling of being seized and burned.

Memory burns. It impresses and imprints like the fierce sunlight that the artist has explored so thoroughly in his most recent paintings. The insights gained from a reading of his country’s landscape as plural also compelled him to pay closer attention to the different intensities of light in particular places, forging compositions that convey with greater clarity his lamentations, sentimentality and hope for a place he grew up in, left and eventually returned to.

It is an enigma that memory is both weight (history as baggage) as well as lightness, at once abstract and particular, mythical and the specific. These contradictions are neither ironed out nor resolved in Wong Perng Fey’s work. Instead they hover as a specter that continuously haunts the paintings and the painter, challenging him to keep pushing for new means in seeking a balance to the scale. This inescapability from memory is the fire that drives him as an artist.

[i] Known also as the Chinese New Villages, these settlements were created during British colonial rule after the second World War to congregate as well as segregate the rural Chinese villagers from early independence insurgents, led by the Malayan Communist Party.