Geraldine Javier and At Maculangan

Green Comes Out Of Blue But Is Richer Than Blue

Valentine Willie Fine Art is delighted to present “Green Comes Out Of Blue But Is Richer Than Blue” a unique exhibition by Geraldine Javier and At Maculangan that stages a dialogue between photography and painting.

The advent of photography, in mid-19th century, has not only usurped painterly concerns with truthful representation but has also introduced different optical perspectives, which in turn, allow painters to revise and invent new visual language. Similarly, early art photography was deeply indebted to the pictorial aesthetic of traditional painting. This exhibition affirms and extends upon a tradition of exchange and cross-influence. It looks at how our contemporary experience is translated into painting by Geraldine Javier and photography by At Maculangan.

Both their works evince a keen insight into the cultural forces that shape the social experiences of Filipinos today. Yet, it is by positioning them together in a space that calls them into conversation with each other that issues and topics ranging from artistic representation to cultural aesthetic are fore-grounded.

“Green Comes Out Of Blue But Is Richer Than Blue” is an exceptional exhibition that will enhance and enrich our understanding of both the conflicting and shared aesthetic sensibilities in painting and photography.

Gothic Camp: A Conversation Between Painting and Photography

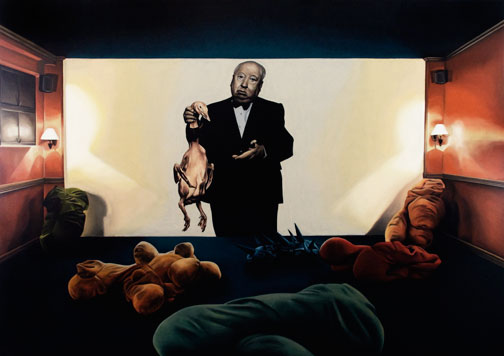

On the far end wall of a cosy room, a photograph of Alfred Hitchcock presenting a defeathered duck taken by fashion photographer Albert Watson is projected onto a blank surface normally used for screening both classic and underground films. The painting Birdwatch by Geraldine Javier is charged with a cine-philic sense of pathos and humour – the funny side of Hitchcock presiding over an audience-less screening.

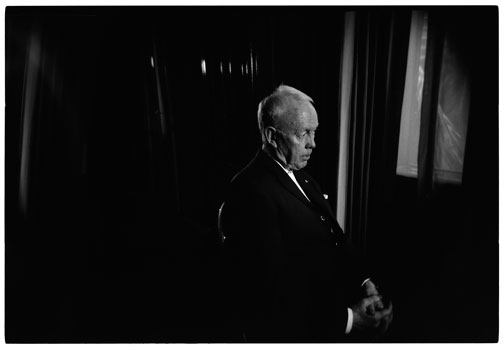

In At Maculangan’s Opera 14, the chiaroscuro effect guards pop psychologist Tony Buzan from the surrounding darkness. As if formed by loose strokes of paint, his hands gleam in the lower right corner of the frame. In this painterly tableau of gloomy contemplation, the positive motivation of an educationalist is weighed down by the negativity of his shadowy environment.

‘Green Comes Out Of Blue But Is Richer Than Blue’ stages a dialogue between paintings by Geraldine Javier and photographs by At Maculangan. They highlight a sensibility that both artists share in spite of their differences in subject and media. This sensibility is the element of ‘camp’ in the gothic.

By ‘camp’ I do not mean the maimed conception of the term as a self-conscious kind of effete irony. It is an attraction towards and a fascination with the transformative power of theatricality, stylisation, and artifice. The gothic with its fascination with preternatural forces is remarkably resonant with camp sensibility. Popular association of the gothic with the macabre has impeded us from recognising two of its underlying principles: artifice and surfeit.

The key sentiment that feeds much of gothic literature and art is neither tragedy nor fear. Rather, it is a tender appeal towards the surreal. To be sure there is a clear element of horror in Dracula and Frankenstein, but there is also sincerity in their theatrical excess, an element of romance and mischief in their narrative that makes them camp.

A style driven by this sensibility is therefore also playful and prone to rule-breaking. Javier and Maculangan display a blatant disregard towards modernist notion of the autonomous medium. On the whole, Javier’s paintings are largely influenced by her interest in film and photography. For example, she painted Birdwatch based on a photograph taken by Maculangan. Maculangan, on the other hand, thinks more like a painter, often referring to his photographs as composites. As such, their ability to think outside of their medium has inflected this dialogue with a shared aesthetic predicate that is larger than life.

By coding the everyday as surreal, Maculangan seems to be suggesting that the flexibility and malleability of the digital medium is more consonant with painterly representation than analogue photography. Often, Maculangan’s photographs betray his training as a painter. Unlike techniques of photomontage, a digitally manipulated image does not usually expose discrepancies when two images are put together in a single photographic frame. Rather, incongruities are smoothed over, producing a singular phantom image that has no real world reference.

By placing his subjects in the middle of the composition, Maculangan is able to emphasise the constructed and fictive nature of digital photography, countering analogue photography’s logic of truthful representation. Moreover, he turns the theatrical spotlights on them as actors of the quotidian. In Opera 11, an image of former Philippines president Fidel Ramos picking up a golf ball is combined with a background image of a razed mansion belonging to the illustrious Lacson family in the Visayas region. Used as an operational base by Japanese army during the Second World War, the mansion was subsequently bombed by American soldiers. Ramos who was almost always photographed as a dignified official is seen here indulging in a recreational pastime, contrary to the air of formality that his public image normally exudes. The ruin looms above an unnoticing statesman, in respite from his political role.

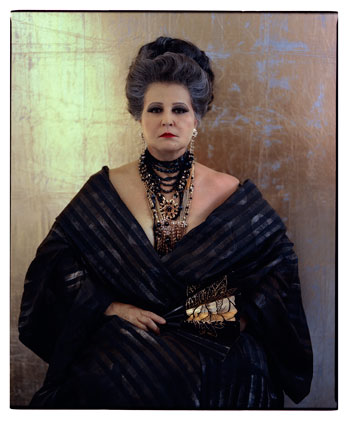

Opera 10 is composed by superimposing an image of a drenched little girl taken at a birthday party with the interior shot of a bedroom located in the historical Lizares Museum. The girl is as if spritely dashing across a sombre diorama of the past, imprinting the dust-settled stillness of the room and the weight of time with the levity of youth. In Untitled, Maculangan dresses up his mother-in-law in an opulent brocade dress. Enthroned under a coiffed wig and bedecked with lavish jewelry, she represents an exaggeration of refinement and a kitsch imitation of the historical past. Covered in a thick layer of makeup, she becomes a figure that is both terrifying and amusing, a doyenne of camp incarnated.

Figurative paintings of our time have been inevitably mediated by iconic images in photography and cinema. Javier’s paintings are sepia-tinted explorations of the enduring and haunting power of this legacy.

Wallflower depicts a wizened Georgia O’Keefe cornered into the flower motif common to her paintings. As an alluring subject for many photographers, from Alfred Steiglitz to Andy Warhol, O’Keefe’s fame rested as much on these iconic photo portraits taken of her as her paintings. Wallflower places the photographically mediated image of O’Keefe in a painterly space to suggest an individuality that is shaped by both painting and photography.

Moonlight is based on a photograph of Sally Mann shot in her studio by a photojournalist. Javier transplanted the artist into a dark haunting landscape, alluding to Mann’s photographic series of the Deep South, published as What Remains. The painting suggests that Southern gothic as a genre is (invariably) linked to its Romantic and Victorian predecessors. By composing the pendant panel as a reference to the wallpaper of an old house, the diptych becomes a house of memories. The missing photographs, the crumbling wallpaper, and the barren landscape suggest an aesthetic of decay and loss, supplying us with a romantic vision of a vanishing world.

Arrangement in Gray and Black refers to the unwavering hold of Diana Vreeland over the world of fashion. Not a person known for her beauty, Vreeland commanded the respect of fashionistas entirely through her sense of style and visionary taste. Javier likens fashion to our outer shells, what we project to others. In Arrangement, Vreeland’s physical form is no longer present; a spectral nightgown haunts us as an inheritance, resting on a couch, above which hang metallic plates adorned with pretty patterns from nature such as seashells, beetles, and a singing blackbird.

While Javier’s paintings provoke a rethinking of our collective culture by alienating the subjects as the mysterious Other, these homages to a world of fashion, film and photography, inflected by a noir-like atmosphere of disquietude, are also deeply tender and clever. For those who appreciate the sensibility of camp that underwrites them, they are pregnant with irony, references and playfulness.

Plucked from a historical fiction by Anchee Min, the title of this exhibition, ‘Green Comes Out Of Blue But Is Richer Than Blue’, is attributed in the novel to Madam Mao. The colour green is comprised of mixing the primary colours of blue and yellow together, a fitting metaphor for the principle of enrichment that subscribes to both the gothic and an allied camp sensibility. Javier describes the exercise as ‘getting influences from various aspects of our lives, distilling and finally making it our very own, while in the process of making art and other things in life.’ i

A notion of play, experimentation, and creation underlies this meaningful engagement between photography and painting. Transforming our quotidian activities and image culture into a spectacle of the uncanny, Maculangan and Javier have found both anxiety and warmth in their subjects.

In a sympathetic conclusion to a sensibility that had attracted and repulsed literary critic Susan Sontag, she movingly declaims, ‘Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of ‘character’… Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as “a camp,” they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.’ ii

Simon Soon

_________________________

i Conversation with artist, 2008

ii Susan Sontag, ‘Notes On “Camp”’ in Against Interpretation, 1966.