Elaine Roberto-Navas

Standing Room Only

“I’d like to achieve a renewed inebriation or reawakening of the everyday. Paul Valery wrote that, ‘Seeing is when you forget the name of what you’re looking at’. I’d like this to happen when viewers see my work.” – Elaine Roberto-Navas, Artist’s Statement

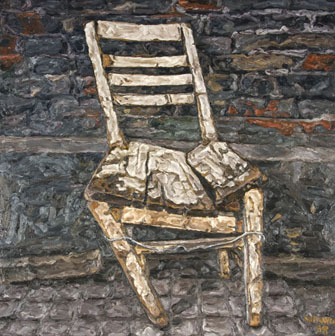

Valentine Willie Fine Art is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition of Filipino painter Elaine Roberto-Navas in Kuala Lumpur. Elaine’s skillful use of colour and texture gives a powerful and sensual life to still objects. Through her signature thick impasto layers of paint, her work, acquire a nervous energy, leading viewers to consider painting beyond the subject matter but also its physical aspect, or ‘materiality’. The richly textured oil paint, layered and crammed on top of one another, almost butter-like, records the history of painting, of how it came to be. These paintings suggest an indefinable, hidden life within the object, and by extension intimate on the human relationship to objects around us: the way we invest meaning to objects and the way objects affect our psychological and emotional state.

Standing Room Only

by Lena Cobangbang

“Perhaps the immobility of the things that surround us is forced upon them by our conviction that they are themselves, and not anything else, and by the immobility of our conceptions of them.” (Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way)

And these things are all part of our daily rituals that gradually accumulate, we are so accustomed to the way we choose things to function that they become an extension of our limbs, our bodies; things that we used to own, owning us back for our dependence on them. Hence, these things take hold of our remembrance.

Elaine Roberto-Navas’ paintings foreground this intimacy with objects, profoundly evoking their association with their previous uses. Her previous exhibition, entitled Garage Sale, at Finale Gallery in Manila, showed a bound bedpost, a wardrobe haphazardly crammed with clothes, a dining table draped with a cloth. Some of these objects were the personal effects of Catalan artist Antoni Tapies that eventually found their way into several of his artworks. Through Roberto-Navas’ distinctly impeccable bravura in handling paint, she has found kinship with Tapies in underscoring the subject’s materiality. More than painting them, she kneads pigment into flesh, turning images into palpable essences.

Her recent paintings are based on a series of photographs by German artist Michael Wolf, of chairs in China that were seemingly abandoned – sitting forlorn, rickety and crooked, mended by some loose rusty copper wire. These chairs under Roberto-Navas’ brushwork are so corporeally rendered yet they tend to melt, threatening to crumble by the gravity of their weathering and neglect if not quickly fleshed out, as if obsolescence is catching up with their memorialisation.

Michael Wolf calls these chairs ‘bastards’ – abandoned, and in some cases retooled to exhaust their function, improvised for the barest needs, to conform to anatomy, or rather matter conforms to need. These can be seen in scraps of mattress bound to a tree stump, a dilapidated swivel chair propped on an empty tin drum, a woven mat lain over a neat pile of bricks. Nonetheless, the quick ‘winging’ from various found materials still offers some brief respite from the quotidian rhythm of work and survival.

Those who labor and sit on these chairs are conspicuously absent, yet these paintings may as well be their portraits. Their craft and ingenuity, their past affluence and their sudden thrift, their misshapen anatomies giving way to gravity and aging can all be possibly gleaned from the very weathering of these chairs.

When chairs were first made, they were meant as furniture solely for the monarchy, or as privileged articles of State. Their descent into commonplace fixtures indicates the spread of specialised skill or labour, and consequently the rise of structures that compartmentalise the different trades arising from such specialisation. The “sitters”, in this instance, have mostly melded into their trade as faceless fixtures in the cog of progress. Through history, formal portraiture has been a means of reinforcing the individuality of the sitter, with all the accoutrements of profit and gain. But for Roberto-Navas, such an approach merely states the obvious. Here the chair suffices – “….to construe the form which its tiredness took as an orientation of its various members, so as to induce from that where the wall lay and the furniture stood, to piece together and to give a name to the house in which it must be living.” (Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way)

The house, it seems, is never shown. It somehow still remains a guarded sanctuary, its whereabouts and placating succor intimated intuitively by its unknown dweller. This becomes apparent in Roberto-Navas’ series of paintings of gates last year, where the very surface of the canvas – heavily marked and swirled by paint, enunciating the incurred scratches, dents and oxidation of the gates themselves. These paintings become stand-ins for the real thing, the gate itself which distinguishes between the “other” and the “familiar”, intrusion from belonging, fortress from a sense of home, a threshold interpolating both exteriority and interiority at the same time. Yet the brilliant luminosity of the paint itself seductively beckons, the surface willing to yield to touch, but only in its tactile suppleness. What can be unlocked are the doors to one’s imaginings underneath these striated surfaces, opening up the possibilities of personal narratives, but at the same time, these are bookend-ed by an ambiguous sense of both disclosure and secrecy, in paintings that hint at the artist’s reluctant admission to autobiography.

These paintings of chairs become boldly privy to much speculative spectatorship as these seats are empty of their sitters. Who owned these seats is but a matter of what they may represent. For the paintings to mirror their creator who sits on a work stool as well upon its conception bears the conceit of authorial prerogative. But for the viewer who can only speculate on the after-effects of the mingling of medium and subject matter, the result is either a fascination for the resulting mix or a fascination for the probability of owning the gaze they set upon it, and consequently their interpretation of it.

If these chairs are portraits, they don’t however naively pander to a “Dorian Gray” idealism, as they bear the consequences and the historical weight of a rapidly-progressing industrialised economy. For the artist, they best serve her distinct mastery of the medium in their dejected forms, pointing out their ‘materiality’ in their variegated destitution and well-worn-ness, and more importantly the tangibility of painting where all things are bequeathed with a stately affirmation of their existence.