Group Exhibition

3 Young Contemporaries

3 Young Contemporaries is VWFA’s annual signature platform created to promote the works of emerging artists from the Southeast Asian region to a wider audience. Over the years, the show has proven itself to be a prominent launch-pad for the careers of many successful artists in the region.

This year’s show will reprise our tried and true formula of seeking out new artistic strategies, encouraging creative experimentation and highlighting the many ways in which young artists are shaping responses to contemporary experience. The 3 Young Contemporaries for 2008 are Ariadhitya Pramuhendra (Bandung, Indonesia), Patricia Eustaquio (Manila, the Philippines) and Tawan Wattuya (Bangkok, Thailand).

3 Young Contemporaries: Patricia Eustaquio, J Ariadhitya Pramuhendra and Tawan Wattuya

Dealing with subjects that are intangible and abstract, the artists in this year’s 3 Young Contemporaries deliver critical and thoughtful explorations on the faculties of our mind that are liquid, porous and perhaps even disquieting to some.

Their works mark a withdrawal from overtly social subjects by turning to a more rigorous examination of the formal attributes of traditional media – painting, sculpture and drawing – as trajectories in charting the prosody of our mind.

The thematic connections that emerge from their art may very well be accidental, although they might also reflect a sort of cultural zeitgeist that informs the methodologies and ideas seized by a new generation of artists that are concerned with contributing to and enhancing artistic practice and discourse, engaging their audience with complex questions about our thought processes.

As the artists uncover the idiosyncrasies of our common sense understanding of memory, imagination and the collective unconscious, they also display an astonishing talent for translating the immaterial mechanics of our mind into visual languages that are both refreshingly intelligent and beautiful.

‘Memory is never absolute’

Intrinsic to memory is its reconstruction of the past through remembrance, and Patricia Eustaquio’s paintings and sculptures are fragile projections of this process. Her artist statement eloquently observes, ‘Every time we try to remember, we have to reconstruct from traces, from things we know. We put things in and leave things out. We stage all these different elements together and play them in our heads so that a memory is never absolute’.

The forms of traces – shells, shadows, fragments of images, floating snapshots – are materials incorporated in Eustaquio’s exploration into the liquidness of memory, in which the relics replay a personal past, that is familiar yet never quite the same, enabling tangential narratives and associations to surface.

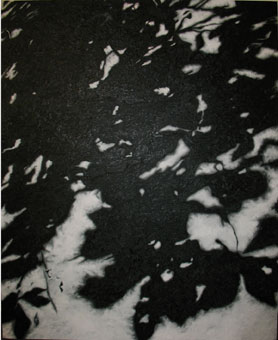

In Pulo, the dapples of sunlight dance hauntingly against a spray of leafy shadows, creating an image that is at once abstract and factual. Pulo in Tagalog means island or islands, and it is also the name of the place where Eustaquio was first impressed with this indelible image that she revisits in her painting. Recognising that the retrieval of things past is an act of reconstruction, Eustaquio’s quiet and poetic aspersions of shadows are continuously layered with new perceptions as her series of shadow painting develops.

Similarly, absence is also indexed in the trace of the crocheted drapes solidified as casts over two chairs, in The Sprinkling and the Pall, existing as their ghostly remains. Its funerary allusion, though mournful, carries a comic undertone. Strapped with neon tubes spelling out the exclamation ‘Oh’ as one of the chairs reacts to the sprinkling of holy water, the solemnity and lifelessness associated with traces and shells are animated by humour and presence.

From the murky depths of memory, Eustaquio transforms her past, ‘weaving a story out of disjunct yet carefully chosen events’, in a practice that finds its creative pulse in the repetition of details and patterns, to create works that hover indeterminately in a state that is on the verge of dissolving through abstraction into a universal narrative of impermanence and loss, yet at the same time yielding clues and shapes of memories that are deeply personal.

Charcoal’s Photographic Imagination

If the works of Eustaquio encapsulate the mutability and instability of memory, Ariadhitya J. Pramuhendra uses charcoal to imitate its representational form in photography, to blur the thin line between imagination and reality. Because charcoal limits the tonal scale of drawings to black and white, its vocabulary allows Hendra to forge a composition that is suggestively photographic. More specifically, it stylistically imitates the black and white photograph.

The photographic condition of the charcoal drawings is therefore indicative of the imagination finding a concrete vocabulary in the past. By mimicking the index register of photography, Pramuhendra’s imagination is concretised, given a sense of history and false memory.

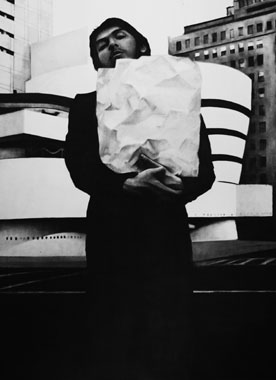

Lost in London and Lost in New York are self-portraits of the artist posing in front of two premier contemporary art institutions, the Tate Modern and Guggenheim Art Museum respectively. Through the lens of these portraitures, Hendra imagines himself participating in a modern day kind of artist grand tour, which is a traditional model of Western art education where the aspiring artist travels all over the world to experience directly artistic masterpieces.

However, its fictive origin belies a feeling of displacement. As an artist working from the periphery of the art world, his proximity and brush with these major art institutions is merely touristic. Even if they exist solely as figments of Pramuhendra’s imagination, the drawings portray an enigmatic though sensitive fictional autobiography on the formative development of the artist’s sense of identity as he attempts to negotiate his place and position, measuring distance and a sense of belonging, within an increasingly globalised culture industry.

Painting the Unconscious

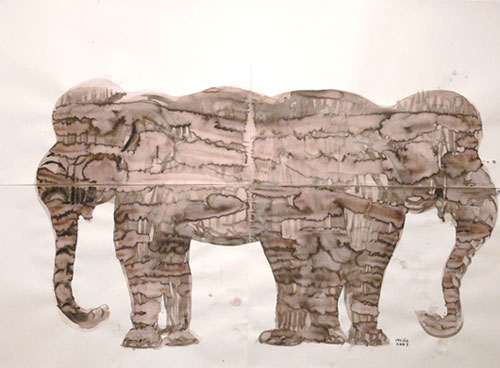

Probing further into the darker recesses of our mind, the figures that emerge from Tawan Wattuya’s paintings are beastly subjects that return to haunt our sensibility. The works in this exhibition belong to a larger series called Siamese Freaks, in which the concept and method of doubling the body threatens the stable identity of its subjects, ranging from porn stars to politicians.

The collection featured in this exhibition is less of a direct criticism of Thailand’s socio-political landscape, compared to other works in the Siamese Freaks series. Rather they are structural illustrations of the archetypal casts that exist in the collective psyche. As the singularity of the subject is rendered multiple, it turns into a pairing that invites comparison and contrast, speaking of the binary codes that it constitutes, revealing the flip side of the coin.

In this sense, Wattuya’s paintings of animals map the notion of monstrosity haunting the collective psyche. The doubling not only intensifies their presence, they also emerge from the pictorial field as monstrous accidents.

Wattuya draws out their hidden presence through painting them. The surfacing of this abnormality is registered in the process, which begins as a layer of soft amorphous patches of colour, formless and irresolute. Working through this cloud of colour, the figures gradually take form through a stream-of-consciousness technique, allowing chance to dictate their final shape.

Rather than occluding the formative processes in the finished work, Wattuya’s paintings expose the stages of its remarkable formation as if he is suggesting that the subjects are themselves yearning for form, for recognition. Perhaps if we consider them as responses from the hidden side of us that is often unacknowledged, their materialisation may be the most honest, although disturbing revelation of the contradictions and complexities that are inherent to our mental make up.