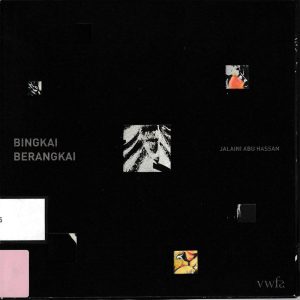

Jalaini Abu Hassan

Bingkai Berangkai

Literally translating as ‘linking or connected frames’, Jai’s latest solo show at Valentine Willie Fine Art is an analysis of storytelling in art. As a process artist, it is natural that Jai’s focus not only embraces the physical acts of making, but also the wider intellectual consideration of how we understand them, which in itself, is also a process.

A painting is a storyboard of ideas, a window into another world, whether in isolation or part of a larger series of images. Sometimes this is clearly narrative and sequential. At others, what we see in front of us is remote and mysterious, with few clues to its meaning. Its understanding, is therefore a process of immediate recognition and/or sustained inquiry to unlock secrets and generate new ideas.

In Bingkai Berangkai Jai emphasises the ‘frame’ – or borders that contain an image. By connecting a diverse system of new paintings, whose interlocked configuration blurs the boundaries of the frame, he encourages an alternative rhythm of interpretation. Increasingly self-reflexive, this complex visual inventory is then filled with chance and opportunity to relate, in new ways, to his observations, imaginings and autobiographies.

WAYS OF SEEING

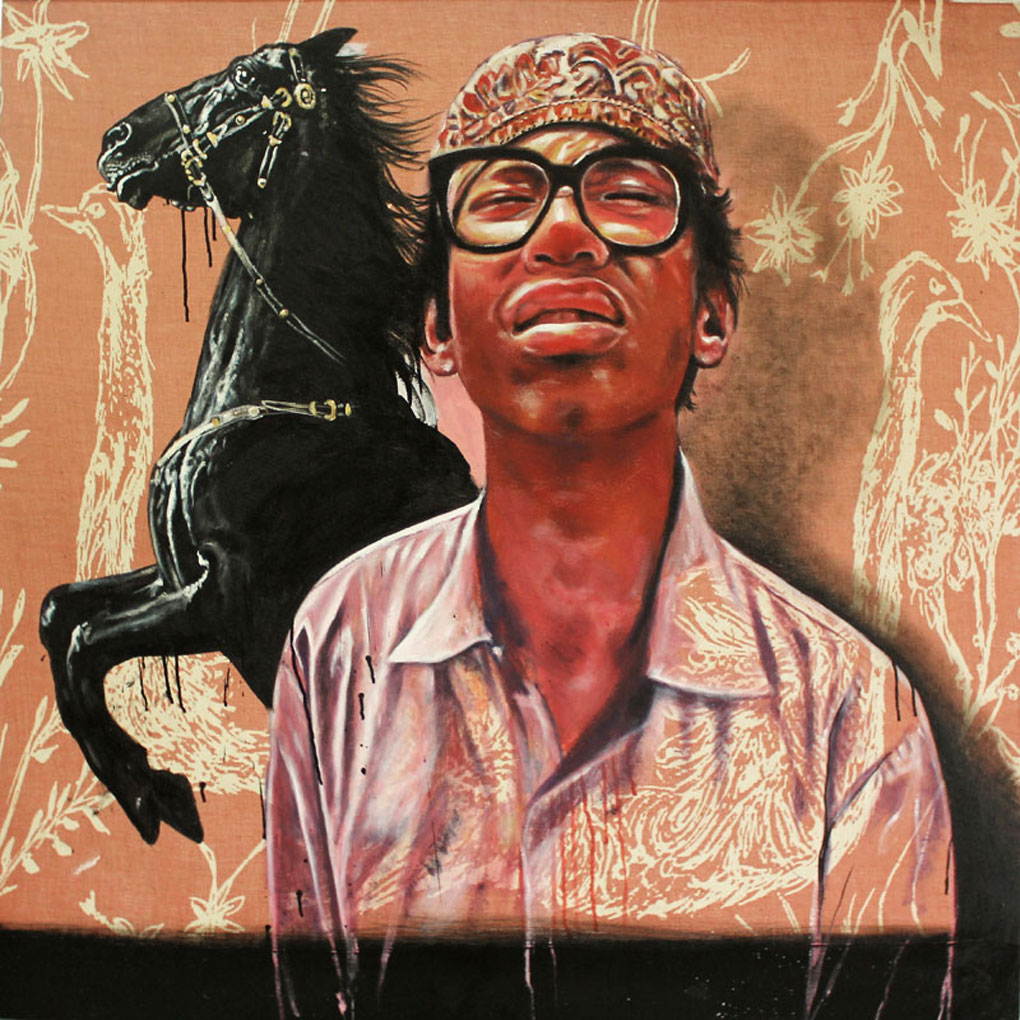

Literally translating as ‘linking or connected frames’, Jalaini Abu Hassan’s latest solo show Bingkai Berangkai at Valentine Willie Fine Art is a deconstruction of visual story telling. Jai is a natural bard, who communicates various narratives through specific figuration and spontaneous mark making. For many years, his painting practice has embraced subjects located within popular culture, poetry, mysticism, Malay culture, social commentary and his own autobiography. As one of the most well-known contemporary Malaysian artists practicing today, his visual stories have subsequently embedded themselves into the narrative of Malaysian contemporary art through his unique formalism and insightful observations on history, politics and cultural identity. However, the gallery experience of his previous bodies of work has tended towards a straightforward exhibition model where works are read individually and as a cohesive self-articulated whole. Discarding this linear format, his latest exhibition brings together a selection of diverse subjects to explore how images can be seen, and the alternative ways they can be visually connected and understood. These spontaneous and purposeful works create an exhibition space where ideas flow in and out of each other, with multiple beginnings, endings and outcomes.

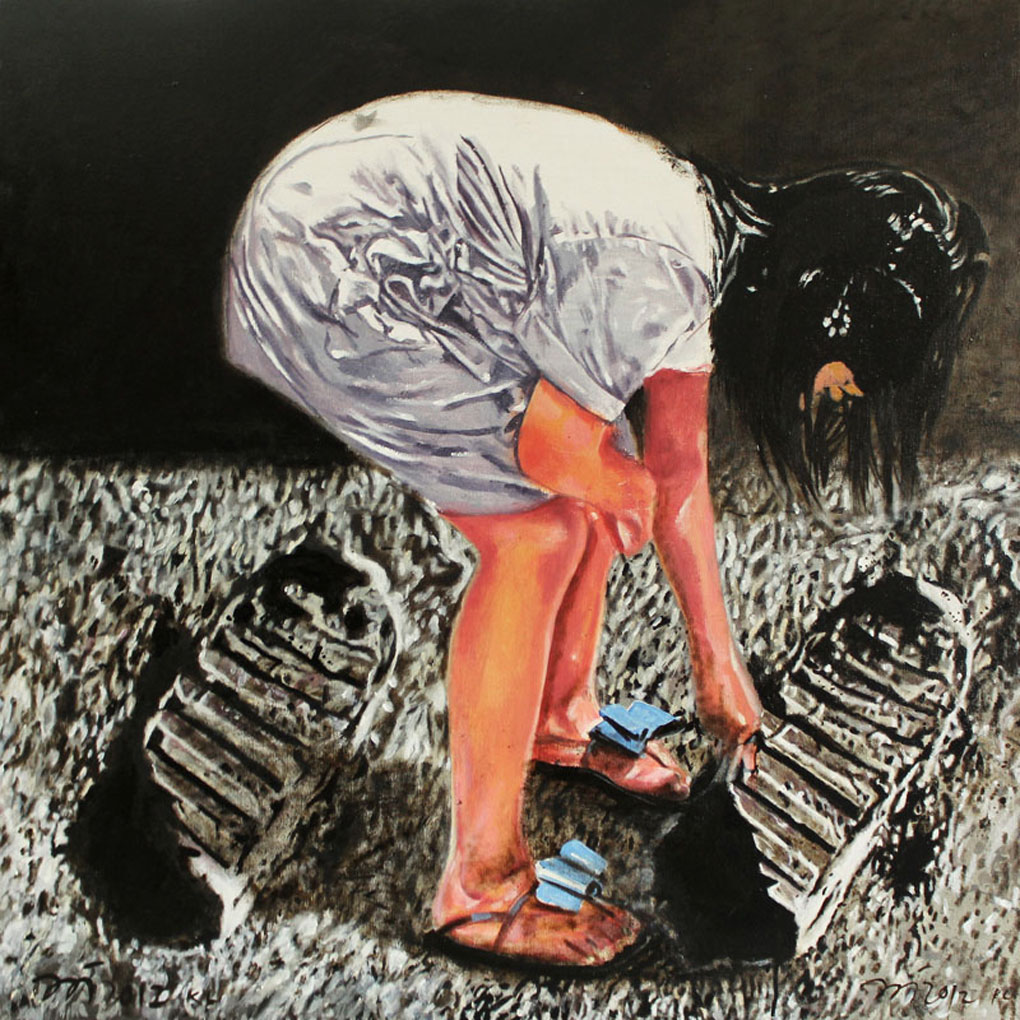

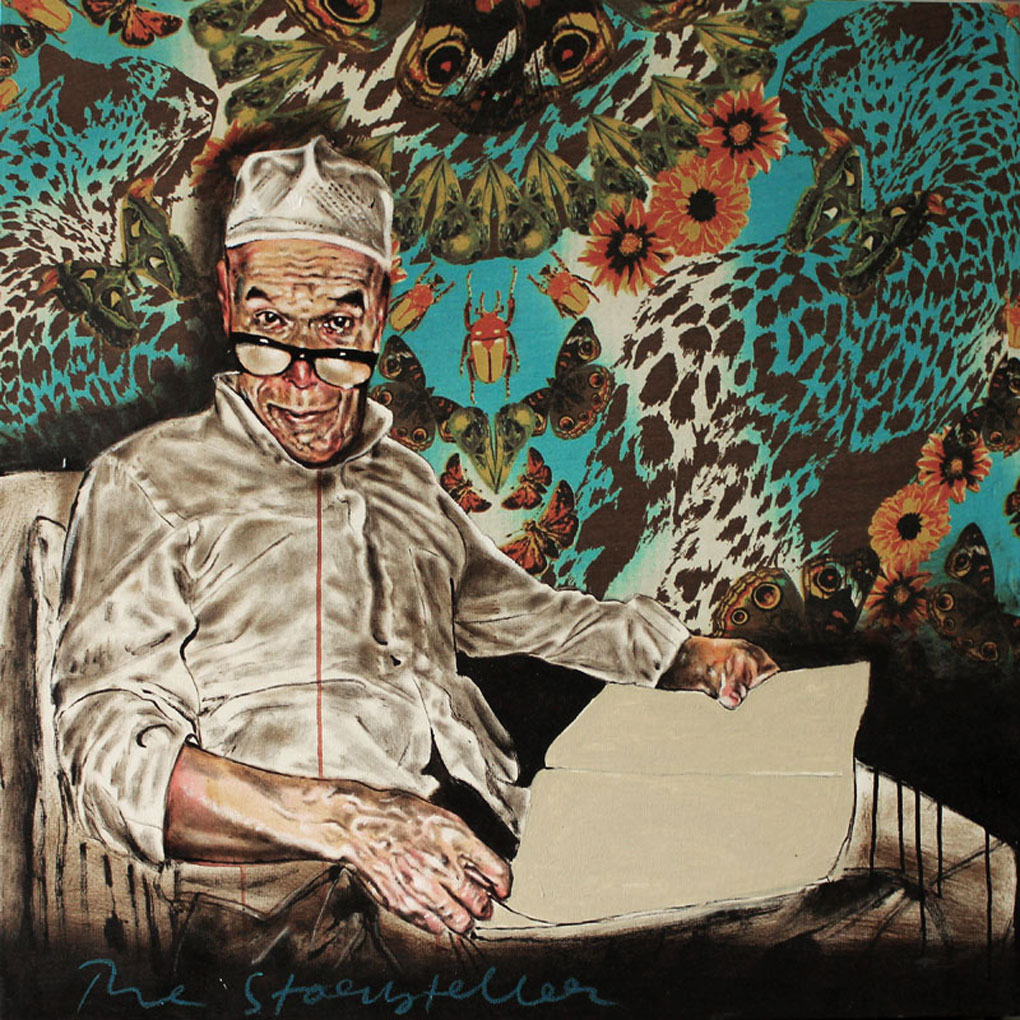

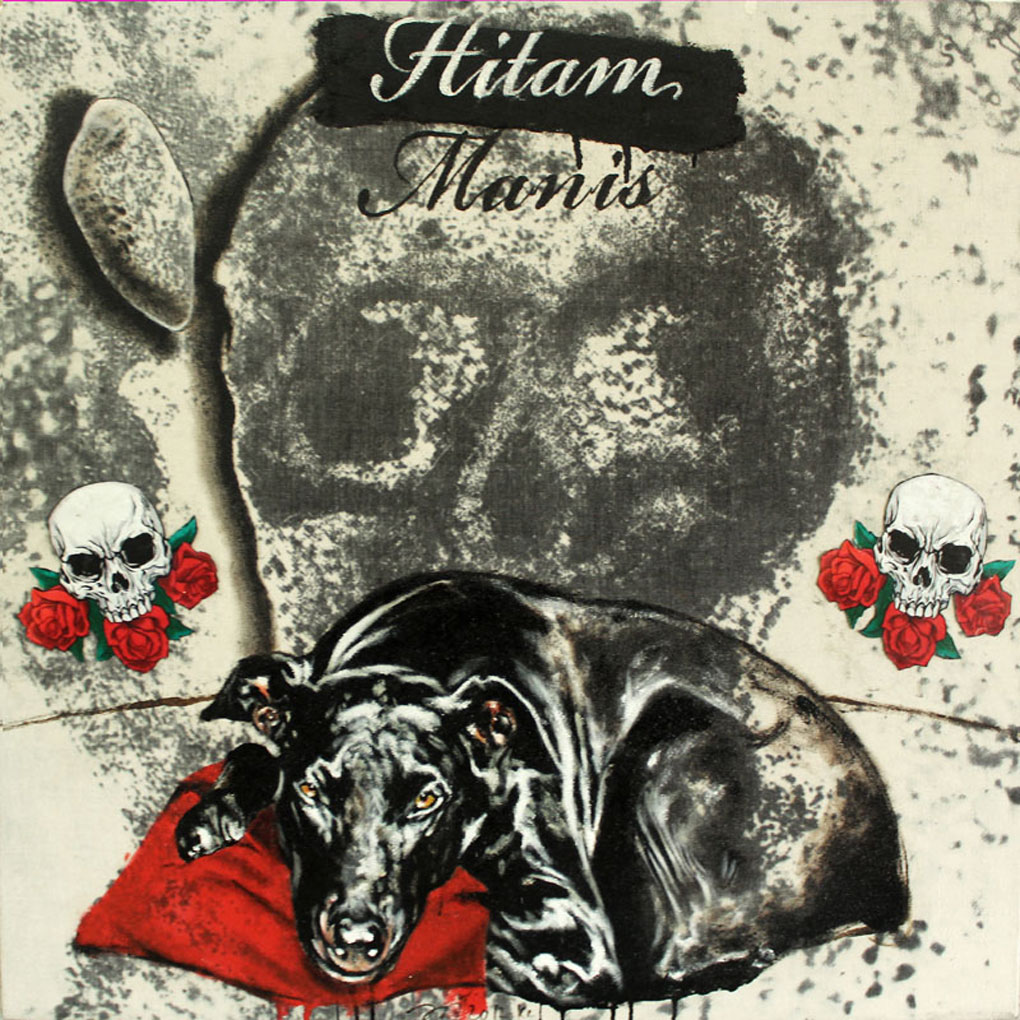

In Bingkai Berangkai, Jai emphasises the ‘frame’ – or the borders that contain an image. By connecting a diverse system of new paintings, whose interlocked configuration blur the boundaries of how images are contained, he encourages a different rhythm of viewing, that is not limited by a specific narrative or the spaces created in between paintings through standard display tactics. Increasingly self-reflexive, this complex visual system of images is instead filled with chance, encouraging new ways of interpretation for his observations, imaginings and personal anecdotes. With no over arching narrative, Jai thus creates a complex ambiguity where the significance of each work competes and distorts the understanding of the next. The responsibility of meaning therefore lies primarily in the selection of the viewer, based upon a relational response, as guided by their own experiences, reference points, and knowledge of Jai’s practice. Images of beetles, beautiful young children, bomohs, storytellers and crouching images of the artist himself, all meet in this visual intersection with titles that only tease at meaning. Further complicating each painting is the introduction of collaged fabrics onto their surfaces. This continues a new line of inquiry for the artist, of using printed and textured fabrics to point his processes into new directions. Each textile is selected for its potentiality of meaning and interpretation, but is intuitively inserted based on colour, texture and weight. A Turkish silk scarf reflects the history of the Ottoman Empire and links various timelines, people and places. However, the lone Malay man in the work, wearing the typical skull-cap of an imam, takes on an ominous significance, when the fabric in the work could be read as a prayer mat and viewers recognise the Russian AK-47 Kalashnikov, lying on the ground behind him. Such conflicts and tensions are necessarily embraced across the exhibition but never at the sacrifice of aesthetic formalism and pictorial balance.

As a process artist, it is natural that Jai not only embraces the physical acts of making, but also the wider intellectual consideration of how we look, understand and interpret images and their stories, which is, in itself a unique process. In Bingkai Berangki he unravels and reconfigures the painting as a storyboard of ideas or window into another world, whether in isolation or part of a larger series of images. Sometimes this is clearly narrative and sequential. At others, what we see in front of us is remote and mysterious, with few clues to its meaning. The selecting of possible narratives is a viewer led process of immediate recognition and/or sustained inquiry to unlock secrets and generate new ideas. Bingkai Berangkai is therefore an experimental gesture to push the boundaries of visual experiences in order to destabilise, challenge and hopefully engage both artist and audience in new ways of understanding the potential of images. The exhibition welcomes the next chapter in an inquisitive and thoughtful career of an artist dedicated to process and form, the art of storytelling and the stories of Art itself.

By Eva McGovern