Chang Fee Ming

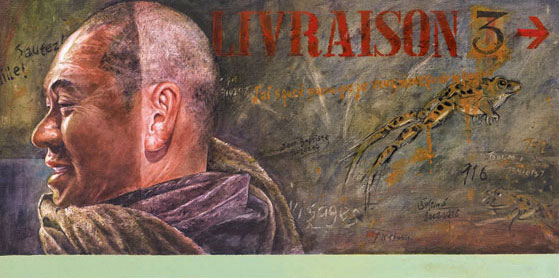

Visage

Valentine Willie Fine Art Singapore is pleased to announce an exhibition of new paintings by Chang Fee Ming – VISAGE. Inspired largely from his recent sojourn to Paris in 2008 as an observer on the film set of Taiwanese/Malaysian director Tsai Ming Liang’s feature length film shot at The Louvre Museum with the same title, Chang Fee Ming takes his abiding fascination with textural surface, the socio-political history of place and his interest in problematising the genre of ‘realism’ to a new level.

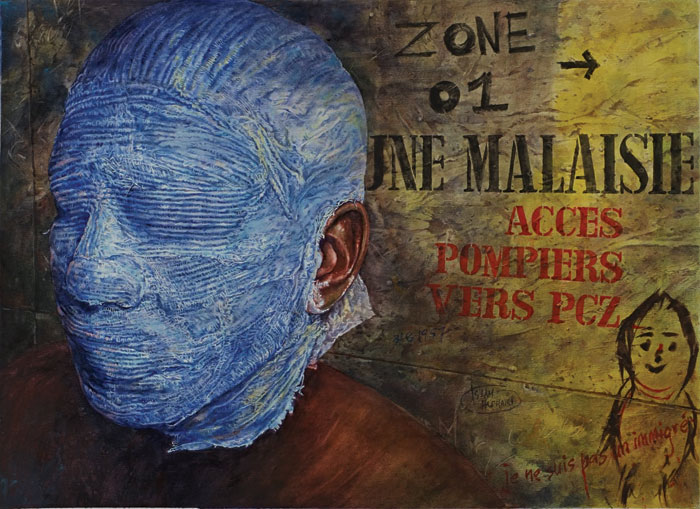

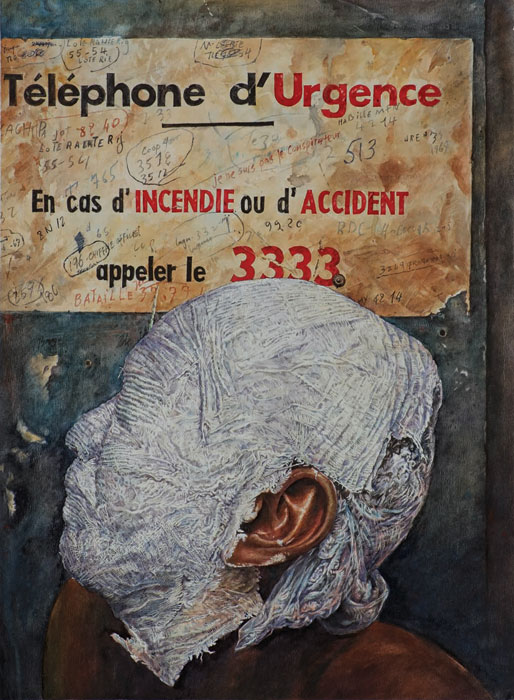

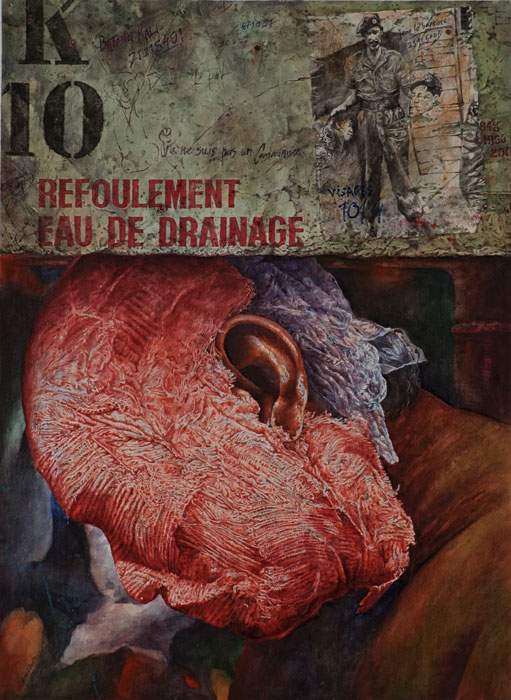

Those who are accustomed to the artist’s lush renditions of the everyday in bucolic setting from the coastlines of Terengganu to the Tibetan plateau will find a different approach in his new series of watercolour. In VISAGE, Tsai Ming Liang’s film set and actors take on a different narrative as Chang Fee Ming appropriates them to tell his own story about the socio-history of Malaysia by combining text and figuration as he merges disparate elements of Parisian and Malaysian iconography.

This surreal collission of time and space is on one level a response to the cinematic language of Tsai Ming Liang and affords Fee Ming with the much regarded notion of ‘critical distance’ in contemporary art through which some of the most difficult issues concerning his country of origin are touched upon.

Favouring the allusive and the metaphorical, the wall has taken the centre stage in Fee Ming’s composition as the graffiti, the language of urban discontent, is employed to highlight social issues and events of the country that never found any resolutions. Cover-ups, conspiracies, intrigues, forgotten atrocities, surfaced and beamed across the wall as coded messages.

While many would consider VISAGE as a departure in a new direction, the exhibition is also arguably an arrival in the sense that the series’s thematic and formal coherence owes just as much to the development of Chang Fee Ming’s practice as Southeast Asia’s preeminent watercolourist over the past twenty five years. The artist’s staying power lies in his flexibility to occupy multiple positions at once, implicating text and image in a slippery production of meaning as well as committing himself to the depiction of different realities through which other stories find a new lease of life.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Chang Fee Ming is the itinerant artist incarnate. Born in Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia in 1959, the self taught artist makes patient records of the realities he is able to capture during his travels.

From the windy Tibetan plateaus to the littoral shores of the Swahili coast, from the farming communities of Indochina to the festivities surrounding Balinese culture, his practice documents, with amazing acuity and depth, the diverse cultural landscapes of the region.

Chang Fee Ming is today recognised as one of Asia’s most accomplished artists working with watercolour. He has exhibited widely in the Southeast Asian region, with solo shows in Kuala Lumpur, Chiang Mai, Singapore, Jakarta and Bali, and participated in numerous major exhibitions in Malaysia, Australia, Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, China (Tianjin and Shanghai), Indonesia, USA, Canada, Hong Kong, UK, Sweden and Brazil.

In recent years, his Mekong series, based on seven years of research and travel, toured to Galeri Petronas, Kuala Lumpur, National Art Gallery, Jakarta and Chiang Mai University Art Museum, Chiang Mai in 2004. In 2005, he travelled to the Swahili Coast in Africa, making a series of small works and studies. From 2005 through to 2007 he has been researching and working on the source of the Mekong, in Yunnan, Tibet and Qinhai. This series was later exhibited in Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Beijing.

In 2009, Chang Fee Ming participated in the artist residency program at Singapore Tyler Print Institute. In the following year, he launched a publication of travel sketches, Sketching Through Southeast Asia, which tells a different story about Southeast Asia than the dominant narrative

that has largely preoccupied itself with the region’s modernity, urbanisation and economic growth.

Chang Fee Ming is based in Kuala Terengganu, spending part of the year in Bali, and much of the rest travelling through Asia.

ABOUT THE DIRECTOR

While many recognised Tsai Ming Liang as one of Taiwan’s most celebrated second generation of ‘new wave’ directors, he was actually born in Sarawak, Malaysia in 1957. He left for studies in Taiwan at the Culture Studies University and have since established his career in Taiwan. Tsai Ming Liang’s cinematic honours include a Golden Lion for Vive L’Amour at the Venice Film Festival in 1994; the Silver Bear/Special Jury Prize for The River at the 1997 Berlin International Film Festival; the FIPRESCI aware for The Hole at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival. His latest film, VISAGE, was commissioned by the Louvre Museum and was nominated for the Golden Palm at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival. It tells the story of a Taiwanese filmmaker’s attempt to make a film based on the myth of Salome at the Louvre Museum. This year, The Pusan International Film Festival will honor Tsai Ming Liang as Asian Filmmaker of the Year.

Face Value

Chang Fee Ming’s staying power, as one of Southeast Asia’s preeminent watercolourists, lies in his ability to occupy multiple positions at once Implicating text and image in a slippery production of meaning as well as committing himself to the depiction of different realities, his stories of the disenfranchised, the marginalised and the unvoiced find a new lease of life. VISAGE while taking his practice in a new direction is also arguably an arrival in the sense that the series’ thematic and formal coherence owe just as much to the development of the artist’s practice over the past twenty-five years.

Those who are accustomed to Fee Ming’s lush renditions of the everyday in bucolic settings from the coastlines of Terengganu to the Tibetan plateau will find a different approach in his new series. First of all, there is the very problematic notion of place, we are never quite sure which world is Fee Ming portraying -scrambled visual codes suggest both his Parisian experience of observing the shooting of Tsai Ming Liang’s feature length film of the same title Visage at the Louvre Museum as well as those that signify Malaysia’s current and historical socio-political problems – whereas in his previous works, the depiction of place is pronounced and direct. Secondly, the shift of subject from the rural to the urban compels the viewer into a different kind of mental space. Gone are the idyll of lapping waves, the rich colours and unhurried movements that suffused his paintings. In their place – stasis, weight, and mess.

Yet there are also continuations in Fee Ming’s abiding fascination with textural surface, the socio-political history of place and his relentless push to problematise and renew our understanding of the genre of ‘realism’ in art. While they may not be immediately recognisable, a closer inspection of the works reveal that these underlying elements form the basis of Fee Ming’s practice and VISAGE’s achievement is in directing our attention to them by constructing a cinematic counterpart, a parallax so to speak, in order to throw them into high relief.

It seems that Fee Ming’s recent sojourn to Paris, filtered through his experience as a guest observer on the film set of Tsai Ming Liang’s Visage, afforded the artist with the much regarded notion of ‘critical distance’ in contemporary art through which some of the most difficult issues concerning his country of origin are touched upon. In some sense, this is always how Fee Ming has worked, favouring allusive and metaphorical codes rather than direct statements. It can be traced back to earlier paintings of his rich accounts of cultural life across Southeast Asia.

Consider Youth and Children Together, which garnered the Gold Award for the Sime Darby Art Asia 1985 competition. Here the presence of school children from a rural community is indexed by the depiction of their footwear and school bags left on the staircase leading up to a kampung house. Fee Ming’s allusive portrait throws into light the question of modern education and how it will shape the future of a younger generation as they take on the new life skills, worldviews and opportunities, that differ from their parents. In Malioboro (1990), the market street life of Yogyakarta is cropped and composed in a manner in which the details of the wrapped batik fabric on the bodies of female traders hiding under a tarpaulin canopy belie the social changes the community underwent. The painting hint at the hardship and labour of women engaged in trade, a transaction that is veiled by the canopy.

In VISAGE however, there is perhaps a new kind of operation set in place that can be characterised as a ‘queering’ of space, which is a process introducing a strange or surreal dimension in order to create a rupture in the dislocation of time and space through which hidden and repressed desires are made to surface.

This strategy resonates with the manner in which Tsai Ming Liang directed his film. In many ways both Fee Ming and Ming Liang worked with the same material (actors and location) though taking it in very different direction. An example of Ming Liang’s film Visage would be how his characters inhabit both Paris locales and the interior of a generic Taiwanese apartment that has been used in many of Tsai Ming Liang’s previous films, as if they belong within geographical proximity. This collision of time and space has been taken to a new level not seen since Tsai Ming Liang’s earlier film, What Time Is It Over There?, which also explores the anxiety of dislocation in Paris-Taipei locales.

However, unlike Ming Liang who works in film where cinematic narrative creates the disjunction and dislocation in time through editing, Fee Ming would have to create this collapse within a single frame. He achieved this by returning to what he understands best, which is the surface.

The surface, for Fee Ming, is an important layer of information. Like the paper support on which the window into his painted world rests, Fee Ming places equal importance on the value of the surface of his content. We may recall the florid arabesque of the batik cloth wrapped against the working body or hung neatly on the clothesline along the breezy shoreline, or the heavy folds of maroon/saffron coloured monk’s robe across mainland Southeast Asia, or still the gnarling and sinewy texture found on both the bodies of men and plants.

This attention to the surface is explored through the overriding concept of the wall in Fee Ming’s urban odyssey in VISAGE. Alongside the cracks and uneven graying surface that make up our public walls, Fee Ming also paid particular attention to the way the wall is a slate for expression and he took to its contemporary language – the graffiti – as a means of confronting us with some of the unresolved issues in Malaysian politics.

Unlike contemporary artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat or Keith Haring who adopted the graffiti aesthetic as a way to create a new language for contemporary painting, Fee Ming’s appropriation stems from a much more critical proposition. He considers it as a site of contestation and resistance against State-sanctioned information, tapping into its most intrinsic quality – vandalism and provocation. In Liberté, Egalité and Fraternité (Liberty, Equality and Fraternity), a suite of three paintings that are connected to each other through the depiction of a sole figure whose face is masked by plaster wraps of red, blue and white colours respectively. Both the colours of the masks and the titles of the three works constitute emblems of French nationalism – the national slogan and the colours of the national flag.

The scenario refers to a film location staged in the basement of the Louvre Museum. Speaking about the location, Fee Ming said that he felt claustrophobic underneath the low-ceiling basement and imagined what it must have felt like for the character in the film whose face was further masked by white plaster. Combining this with the visual registers found on the basement’s signboards, the scrawls manifest both existing graffiti writings as well as slew of texts and numbers referring to the socio-political climate of Malaysia. Phrases and words such as Batang Kali, Je ne Suis Pas un Communist (I am not a Communist), Islam Hadhari, Une Malaisie (1Malaysia), je ne suis pas le conspiratuer (I am not the conspirator) hint at the ferment of incidents and issues that are largely unresolved, left as a mystery.

In Rolling, Rolling, Action! Tsai Ming Liang’s directorial hand gesture is framed against the backdrop of a graffitied wall found on the riverbank of the Klang river in Kuala Lumpur. Cover-ups, conspiracies, intrigues, forgotten atrocities, surfaced and beamed across the wall as coded messages exist as a texture on the surface – impenetrable and mysterious.

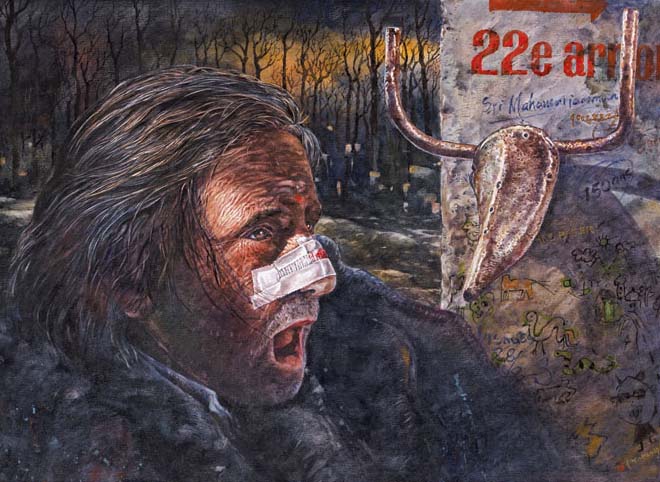

Resonating with Fee Ming’s earlier concerns for the lives of the ordinary people across Southeast Asia, the socio-political history that impacts upon the everyday sphere of living is also explored in VISAGE. In La Vache! (Holy Cow!), which features an expression of an aged French actor Jean-Pierre Leaud seemingly shouting across a desolate landscape, the wall adjacent to where he stands also hangs the famous sculpture by Picasso, Bull’s Head (1943). Referring to the parading of a slaughtered cow head as an act of protest against the relocation of a 150-year-old Hindu temple in a Muslim majority neighbourhood, Fee Ming connects the aggression with Picasso’s Bull’s Head to examine the question of representation and symbolism and how it plays out in the political arena.

Similarly, inspired by Jiang Rong’s best-selling novel Wolf Totem, Fee Ming found resonance between the totem animal of the Mongolians with the mystery behind the murder of Mongolian model Altantuya in Malaysia. He plays them out in a dark cavern where the source of light that shines through crevasses illuminates the texts on the papers covering the window as those taken from French journalist Arnaud Dubus’s highly controversial reportage of the incident.

On another note, in Sautez, Grenouille! Sautez! (Jump, Frog! Jump!) the currently popular “defection” game played by both the ruling and the opposition parties in Malaysia, which led to the 2009 Perak constitutional crisis and sparked a nation-wide debate on the issue of ‘party hopping’ symbolised in the national imagination by the frog.

These issues, coming into play in VISAGE, hint at how truth when repressed are transformed into barely audible and legible signals that continues to encode itself in an arena where the possibilities and probabilities of its discovery continue to haunt our consciousness and conscience.

Moreover, what came out from VISAGE as it dipped itself in another locale and challenge our familiarity with both the subject of Fee Ming’s paintings is that it casts the genre of realism in new light. Previous writings such as the essay by Christine Rohani Longuet have considered ‘light’, ‘movement’ and ‘transparency’ in Fee Ming’s works or artist Wong Hoy Cheong’s acute observation on Fee Ming’s ability to skillfully maintain the equilibrium between translucence and materiality through his painterly techniques in his unique handling of the watercolour medium. However by turning his Parisian experience into a surrealist tableau where the Malaysian stories emerge through its film setting, Fee Ming seems to have highlighted the constructedness and the cinematographic language of the genre itself, how realism is never synonymous to en plein air painting despite its naturalistic style of representation, but requires the artist to compositionally frame, direct and stage his paintings.

Take L’Appat (The Bait) as an example, which shows a tightly cropped torso of a man wearing a codpiece. Next to this hangs a bait with an eggplant hooked onto it. There is also a black and white photo in the background, taken from a film

location in the Jardin des Tuileries (Tuileries Garden) next to the Louvre Museum, which is known as a popular cruising ground for homosexuals. Finally, a writing on the wall boldly reads in French a translation of a highly contentious headline in a local newspaper, ‘I don’t want to be sodomised again’, These elements fall into place in order to suggest the homoerotic undercurrent and violence that permeates Fee Ming’s allusive pictorial narrative of the sodomy charges against the opposition coalition political leader Anwar Ibrahim.

In Le Victime (The Victim), the figure of actor Norman Atun playing Jean Baptiste crouched in fetal position in a dungeon resonated with the death of Teoh Beng Hock. The outline of Teoh Beng Hock in the position of his death as he mysteriously fell off the Anti-Corruption Agency’s building can be made out on the dungeon wall. Here Jean Baptiste’s incarceration throws into light the abuses of human rights through a biblical narrative.

Perhaps what makes VISAGE such an interesting project is that it is a kind of bifurcation – the splitting of a single substance into two different eventualities. By working on the same material as Tsai Ming Liang, Fee Ming seems to have cinematographically directed his own ‘film’ in his paintings through a grammatical inflection that responded to Tsai Ming Liang’s surrealist spin on the subjects the latter works with.

This playful recoding brings to light what Fee Ming understood to be Tsai Ming Liang’s method of working, dialoguing with it in painterly terms just as much as it deconstructs the genre he works with. Materials opening up towards different streams of possibilities and potentialities, yielding narratives that are have been taken to their absurd conclusions, result in a much more rewarding kind of comment on the contradictions of our reality. It rewrites what ‘realism’ is, beyond our commonplace understanding of its naturalistic impulse, by placing importance on the cinematic values that come to bear on how we frame our everyday, how we tell our most gripping, nasty, dirty stories about ourselves that need to be communicated to the world.

Simon Soon