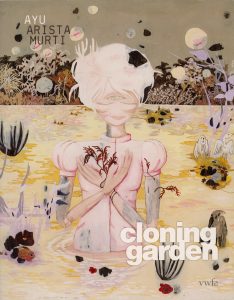

Ayu Arista Murti

Cloning Garden

In Cloning Garden, Ayu Arista Murti takes us into the future, a time filled with hope and optimism; where human beings live in harmony with the nature. But instead of presenting the classical and stereotypical depiction of nature, Ayu wants us to deal with the planet we live in now.

The idea for Cloning Garden may have been inspired by the ambitious green campaigns that have evolved as a dominant presence in the last five years. There are many movies and stories that have been made recently on this topic, including Al Gore’s notable documentary An Inconvenient Truth that exposed the danger posed by humanity to environmental sustainability. This type of exposure has brought environmental issues into mainstream contemporary discourse. Global Warming is now part of bombastic corporate advertising and events designed to promote corporate social responsibility programs, responding to the assumption that large scale corporate practices are the causes of environmental destruction.

Ayu takes personal approach to this matter. Cloning Garden thus becomes a story and dream towards healthy and sustainable human life. Ayu does not talk about specific environmental issues as discussed in mass media, but captures this issue in a scope that goes beyond the environmental discourse itself. In Cloning Garden, she tries to retrace our relationship with the earth—as the place we live within, with its complex history—and also our relationship towards the meaning of human life itself.

By presenting her new works in this series, Ayu invites us to reopen our past through the romantic undertones of time and memory. Ayu also underlines the important role of women in order to make the earth a healthier and more balanced place. Even though their efforts are considered as small, personal, and domestic. Her visual imagery might remind us of children books, where we accept visual symbols faster than words.

Ayu Arista and the Hopeful Land by Alia Swastika

I often read in fairytales and myths, how women embody the role of caretaker and guardian of the universe. Being Javanese—in the sense that I live in Java— I frequently heard as a child, the story of Dewi Sri, the figure of the land, who is highly respected by farmers. To celebrate her spirit, rituals are prepared in the hope that her soul will fertilise the land and bring prosperity to the people (in Indonesian this is called gemah ripah loh jinawi).

However, although interested in the relationship between women and the land, Ayu Arista does not discuss such past mythologies in her latest solo exhibition Cloning Garden. Rather, the artist takes us into the future, to a hopeful time, where humans and nature live together harmoniously. Instead of echoing current rhetoric that tends to stereotype nature, she proposes an optimistic and inspiring state for the world we live in today.

The exhibition reopens our memories about a time that may seem primitive, where women had an important role, however small or personal, in making the earth more lush. This perhaps reminds us of the long lasting impressions from childhood storybooks, since visual memory leaves deeper marks in the subconscious than text. So let us ‘read’ the picture book Ayu has created.

****

I do not know how the importance of women’s role in relation to nature has become so reduced within established knowledge. For some reason, there are very few stories of present-day women who fight for the balance of nature against humanity’s abusive tendencies, which I consider as displaying masculine mannerisms. Of course, there are heroic examples of women such as Vandana Shiva or Arundhati Roy in India that have inspired many people and the popular blockbuster film about Erin Brockovich serves as yet another reminder of female triumph over corporate exploitation of communities and the environment. However, do we really have to be that heroic to consider the relationship between women and nature?

In the journey of human civilisation, women are recorded as the main figure in nature’s cycle, especially because they are (constructed to be) responsible in roles related to gathering food and simple fuel. For that reason, it was women who maintained knowledge about nature and soil; how to fertilise, make compost and grow crops. Then with the birth of technology, men took ownership over this knowledge, enforcing new systems that changed the female relationship with nature.

Vandana Shiva, an Indian environmental activist, believes that in the cosmology of India, the world is created and continuously renewed through a dialectic process of creation and destruction, cohesion and disintegration. Hence, what the modern human race should be aware of is how to give new meaning from that dialectic process, in a time where one (destruction) is more dominant compared to the rest. According to Shiva, women are in fact losing the opportunity to practice their remarkable privilege as the guardian of balance, a role which is recognized biologically, socially and culturally in various societies. In the past, women distributed richness from rough jungles to the farm and its animals. But the masculine modern concept diminishes such ‘matriarchal’ process because the cultivation of land is done with destructive and aggressive dynamism.

****

Ayu’s idea for Cloning Garden is probably influenced by the unceasing environmental and green campaigns that have now become the dominant rhetoric over the past five years. Subsequently films on environmental damage, including the documentary An Inconvenient Truth by Al Gore, have also brought activist discourse into the mainstream. As such global warming issues are now the popular subject for elaborate marketing and corporate social responsibility programs. Ironically such corporations are seemingly the main perpetrators of the severity of the earth’s condition today.

Ayu begins to review these issues from a more personal approach. Cloning Garden highlights the artist’s dreams and hopes for a healthy and humane living space. She maps out several significant biological and environmental issues such as human cloning, dry lands and a calamitous earth, as well as the animal kingdom and its loss of habitat. However, she is not talking specifically about current environmental shifts or headlines in the mass media, instead, she looks at these issues within a framework, which, in my opinion, goes beyond the environment as a discourse. As such, in Cloning Garden, we are invited to retrace our relationship with nature—as a living space that we occupy, which has its own history—as well as the complex repercussions of developing civilisations.

For me, what’s interesting is how Ayu places views on nature and the universe in a rather ‘feminine’ framework, which reveals again women’s role as nature’s guardian and protector. This role, in contemporary sociological studies, is often designated as a domestic role associated to women. I think, and this was confirmed by Ayu herself in one of our conversations, that awareness on social issues is something that develops at the same time to when motherhood begins. After giving birth and raising her child Nabiel, she then began to ruminate on the living environment for future generations. Through this more personal sentiment, she starts to explore the questions surrounding humanity and the universe.

In the matter of humanity, for example, Ayu is interested in the issue of cloning, which not only involves a medical aspect, but also deals with moral debates and existentialism philosophies. Rather than taking the pretense in determining whether or not cloning has a positive influence on human civilisation, she looks at the events of discovery and discourse by identifying her own experience as a mother; where there are biological processes that involve a bodily occurrence, and an actual experience in raising and educating a child; a process where knowledge and life experience are transferred to the next generation. The trouble of the cloning discourse, from Ayu’s point of view, is how the collective education process of the society and families, oftentimes unpredictable and variable, could then become more predicted because the human qualities are now constructible almost certainly due to knowledge and technology.

Ayu is also interested in the effort of creating a healthier personal living space. Having her own land, she grows her own basic herbs and vegetables such as tomatoes and chillies. This kind of practice, in a broader framework, in my opinion becomes some sort of attempt to bring environmental issues back to the personal realm, reestablishing the relationship between women and nature. These domestic roles, although often pejorative in meaning in relation to feminist issues, still reinforce the female position in maintaining the survival of the universe.

Personal approaches in Cloning Garden show how a discourse turns into action, in a smaller and more practical scale. In the world of art, which now is more distant and filled with paradoxes related to expediency issues raised by artists for a broader interest, this kind of approach by Ayu, in my opinion, becomes relevant but provides few answers. In the context of contemporary arts, such messages are especially valuable in order to view how artists are still making an effort to communicate with their audience. An artist’s tendency to be lost with themselves and their own thoughts causes a distance between contemporary arts and the public. Ayu therefore, seeks to establish communication by conveying something that is a common and shared issue.

If during the 1980s and 1990s, these messages always turned political, in order to overthrow a mutual enemy, then for the past five years artists tend to speak within a more personal realm that concerns individual matters. The awareness to take part in creating a healthier living environment surely has its own complex political dimension, but Ayu seems to be more intent on emphasising how humans as individuals must have a personal awareness to be responsible for their living space. Therefore, Ayu purposefully does not enter the complex area of environmental politics such as the country’s policy on land and earth management, or how foreign companies undermine and dispose of waste in a massive scale.

Perhaps, Ayu’s chosen approach is rather ‘feminine’. However, today, in the realm of cultural studies there is such a thing called strategic essentialism, where certain qualities such as femininity and masculinity are not measured by the essential usage, but based on the strategy to achieve certain goals. Ayu applies femininity to reestablish how women hold a significant role in the environmental movements within the domestic sphere. I, with my identity as a woman, share the same dilemma and concern with her. In a way, this reminds me of how every household decision taken by a woman has a direct effect to the surrounding environment.

****

Looking at the series of Ayu’s paintings, I am taken to a fairytale world. For a long time Ayu has been interested in creating images that evoke fantasy, a kind of bedtime story with recurring allusions to science fiction. Perhaps the usage of visual symbols by Ayu, particularly the human figure, used to be considered as frightening like those in the horror stories. At first this bothered her, because what she emphasises is not human fear but rather emotions from within that are psychologically pressured. These inner feelings are in fact more complex than fear, and have more existential implications.

Previously, Ayu worked with darker and more transparent colours. After focusing on a narrative and minimalist visual language, Ayu now displays a new specificity which I think is representational of her current identity, both as an artist and as a woman, particularly featured in many elements that are now more mature. Besides using more colours, to counter balance her grim and horrific impressions, Ayu also uses more communicative symbols. She also experiments with brushstrokes, which are now transparent and given watercolour-like effect or applied like markers allowing for a varied light and heaviness of stroke.

The human figures that she creates still have a connection with her former approach. However, I think it is also influenced by her current thematic choices which give these strange and unusual figure a more relevant context. Her frightening and gripping tensions transform into a whole different image, which, as I stated in the beginning of this curatorial piece are hopeful and, perhaps, rather cheerful.