Jalaini Abu Hassan

Dendongeng

Valentine Willie Fine Art is delighted to present Jalaini Abu Hassan’s long anticipated solo exhibition in Kuala Lumpur, Dendongeng. Jalaini (also known affectionately as ‘Jai’) has in the past three years busy himself with two successful solo exhibitions in Jakarta and Singapore, which has significantly increased his prominence and reputation within the regional art scene. Dendongeng heralds Jai’s return to Kuala Lumpur by presenting a new series of paintings that mark the development of the artist as one of Malaysia’s foremost proponent of Pop.

Inspired by larger than life characters of Malay literature and folklore, Dendongeng highlights Jai’s skilful employment of the pop vernacular to rearrange, reinterpret and retell new versions of these age-old tales. Through appropriating styles and techniques as broad-reaching as Renaissance chiaroscuro to Pop art’s treatment of the canvas as a flatbed to new exploration of bitumen medium as paint, Jai invents a new classical dialect to complement his visual narrative.

Dendongeng is a marriage of two Malay words, Dendangan (a graceful style of presentation, commonly in the form of singing) and Dongeng (myth or legend). Jai explains, ‘Besides its unique rhythmic resonance, the word Dendongeng is in my mind reminiscent of the infamous onomatopoetic phrase, Jeng-jeng-jeng!, a stereotypical tune used to evoke suspense in local movies.’

From bearded civet-cat to Mat Jenin the dreamer, to Badang the eater of a demon’s vomit, these stories are given a contemporary spin by highlighting their relevance to our present times. Dendongeng is the fantastical dramatic paradox that tells story of our country.

Notes on Dendongeng

The stories that we inherit, that acquire new meaning and context as we internalise them and then take on new resonance as we pass them on is one way of describing what Dendongeng is about. In Jalaini Abu Hassan’s twentieth solo exhibition, the aesthetic dissonance that has come to characterise the imageries that appear on the artist’s canvas demonstrates and finds its origin in the artist’s long lasting fascination and love for Malay literature and folklore.

This new body of paintings came from the stories Jai tells his children. ‘I tell them stories I used to hear from my mother. Because storytelling is an oral custom, you’ll always invent new details along the way. These stories have been passed on from one generation to another, mother to child, teacher to student. There’s always an element of exaggeration and drama in them. You never ask if it is true or false, whether one version is purer than the other. When you educate people with stories, the important thing is the moral of the stories and the fun that comes along with telling and listening to them.’

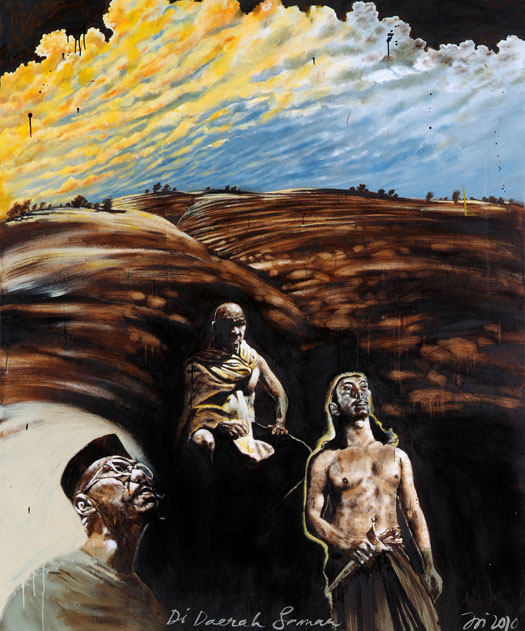

Dendongeng marries two Malay words, dendangan (a graceful style of presentation, commonly in the form of singing) and dongeng (myth or legend), in a portmanteau that describes the allegorical and performative nature of Jai’s paintings. Allegorical in the way it recast traditional folklore in contemporaneous terms and performative in the way Jai works with bitumen – teasing out figures, images and forms from the messy marks that stain his canvas.

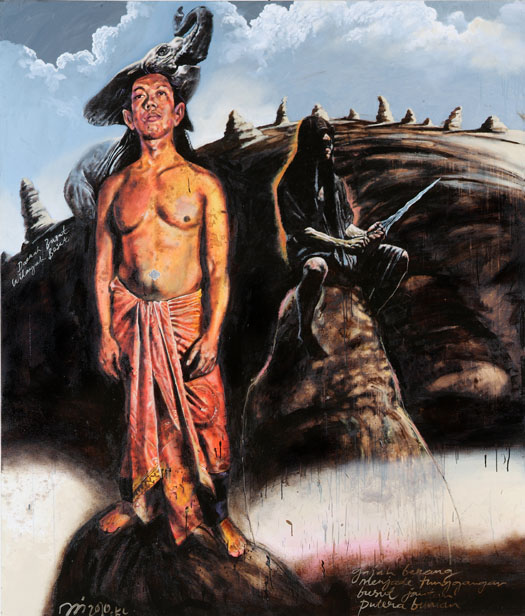

Inspired by larger than life characters of Malay literature and folklore, Dendongeng highlights Jai’s skillful employment of the pop vernacular to rearrange, reinterpret and retell new versions of these age-old tales. Through appropriating styles and techniques as broad reaching as Rennaissance chiaroscuro to Pop art’s treatment of the canvas as a flatbed, Jai invents a neo-classical dialect to complement his visual narrative. From bearded civet-cat to Mat Jenin the dreamer, from Badang the eater of a demon’s vomit to the Putera Bunian, these stories are given a contemporary spin.

A sense of mischief permeates Dendongeng, just as how the content of these stories is generally playful in character. Jai performs the part of a penglipulara, the storyteller who wanders from village to village to enchant and amuse as well as to provide timely instructions about the social values that are embodied within these fantastical tales.

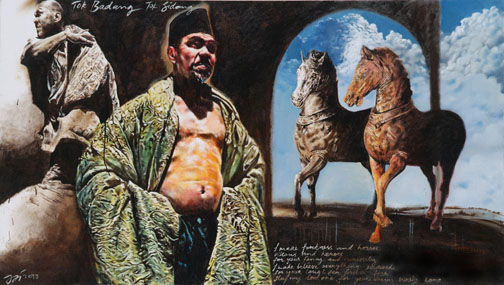

In Badang Bersidang and Tok Badang Tok Sidang, Jai casts himself as the legendary Badang who according to legend despite being born small-framed and weak attained supernatural strength after eating a demon’s vomit. Because of his newfound power he was accorded great respect and spent the rest of his life helping others. Badang is described as a ‘pembuka gelanggang’ or a ringmaster, for he represents the overcoming of one’s fate and becomes the master of his narrative. In both paintings, Badang is portrayed in his element, playing the part of the self-assured leader who is able to determine the course of his destiny.

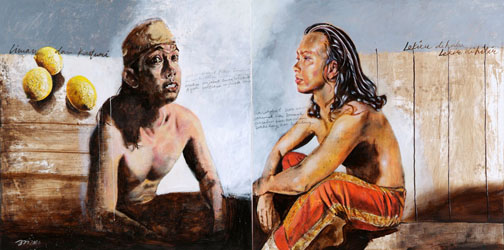

In Putera Bunian, we see the prince of fairy towering over a field of busuk jantan or anthills, which is traditionally regarded as his sacred abode. Above one of the anthill sits a pennungu or a watcher, the dark guardian who waits and protects over sacred ground. Elsewhere Hang Kasturi and Hang Lekir in Limau and Kasturi are depicted in conversation, the sidelined warriors in the history of Malay literature are given prominence here as protagonists to suggest the possibilities of relooking at a fertile narrative thread that is still undeveloped.

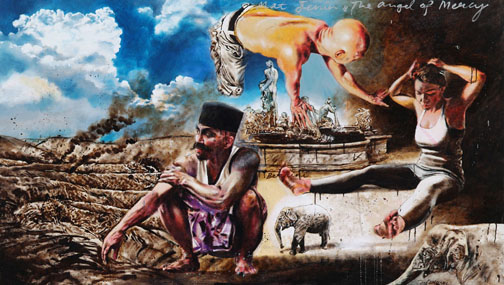

Jai also finds himself in this sense playing the role of Mat Jenin the dreamer in Mat Jenin & the Angel of Mercy whose dreams carry him beyond the confines of his own world into the fantastical realms replete with Italian fountains as well as modern tin mines. In this particular painting, both time and place is conflated within the same visual plane to underscore that the dreaming reality and its imaginative potential is far-reaching.

Furthermore, references to Renaissance paintings in terms of subject such as in Tok Bandang Tok Sidang and Mat Jenin & the Angel of Mercy as well as modes of painting such as chiaroscuro and sfumato highlight a unique adoption and transference of a Western aesthetic vernacular into a local painterly discourse that complicates what we understand to be modern Malaysian art. Having moved beyond the concerns of early modern post-colonial artists who rejected Western idioms in favour of a localised expression, Jai flagrantly acknowledges the complexity of our received tradition that is rooted in hybridity rather than purity.

In spite of its apolitical exploration of Malay culture and identity, the works seem like a timely response to the recently renewed culture war, such as those rallying call to arms in organisations such as PERKASA, which has defined Malay identity and culture within a narrow purview. The fluidity of these stories and their openness to play as each succeeding generation absorbs them and pass them on shows us how tradition as transmission of customs and beliefs is always in flux.

Culture is cosmological. Like the landscape that looms across all the paintings in Dendongeng, these realities underwrite our landscape, they shape our sense of belonging to a place and to a land and how we understand them. In the bigger picture, it is also like the tree of life, which takes root above our everyday world in Pohon Hayat Hujan Setempat. The sum of our culture is always larger than our need to circumscribe it within a specific set of political agenda. Rather than locate an untainted origin to these tales and claim them within the confines of specific cultural spheres, Dendongeng carries the lyricism of these tales like a pop hit that infects and shapes the lives of Malaysian across the ethnic divide.

This exhibition is markedly different from his two previous exhibitions, which I also had the opportunity to write about. Unlike Chanang (Jakarta, 2008), which explored and pushed the tenuous boundary between the Islamic concept of permissibility (halal and haram) in image making, or Bisik Menjerit (Singpore, 2009) in which the urgency and need to address the Perak political crisis saw a stylistic turn towards the farcical and carnivalesque, Dendongeng departs from the need to directly acknowledge present day socio-political concerns in order to examine a much more abiding and difficult question of how do we situate figuration in Malay visual culture.

This is of course nothing new. The history of modern art in Malaya and Malaysia is the story of how we inherited a new mode of representing our realities. Islamic principles that have informed pre-colonial visual culture in Malaya for the preceding five hundred eschewed realism in favour of abstract stylisation.

Early British influence however saw Penang artists such as Abdullah Ariff and Singapore based Lim Cheng Hoe focused on landscape paintings. It was Javanese-born Hossein Enas, no doubt familiar with the works of Indonesian master realist Raden Salleh, who established one of the longest traditions of figuration through his artist group Angkatan Pelukis Semenanjung (APS), which sought to capture the essence and dignity of our local subjects in their figurative form.

In spite of how subsequent modern art movements came to challenge figurative mode of paintings in Malaysia – such as the abstract and expressionist painters of the Sixties, who sought to convey the spirit of the modern through non-objective means as well as the Islamic formalist in the early Eighties who employed Islamic aesthetic and values as guiding principle in the process of art-making – the figure persisted.

Jai could be counted alongside Kok Yew Puah, Wong Hoy Cheong, Matahati Art Collective as the new wave of artists who brought figuration back into prominence in the late Eighties and early Nineties. Later as a lecturer at UiTM, he had influenced the creative direction of many young contemporary painters who continue to practice today, fathering a generation of figurative painters in contemporary Malaysian art.

Figuration as a way of seeing our world and representing our ideas have been employed by successive generations of painters who took advantage of its allegorical possibilities as a way of characterising the ethos of a particular time and place, to tell its stories. Through Dendongeng, Jai’s figures acquire monumental significance. The figures are no longer solely an actor in our day-to-day reality; they too inhabit and come to shape our older stories, our oldest dreams, reaching back into time immemorial. More importantly, these figures draw the stories back into our present day, performing in a contemporary language that recreates our perennial drama for the entertainment, amusement, and moral edification of our future audience.

Simon Soon