Zheng Chongbin

Emergent

Valentine Willie Fine Art is pleased to present EMERGENT, a solo exhibition by San Francisco and Shanghai based Chinese American artist Zheng Chongbin. In this show, Zheng will be exhibiting both his signature ink paintings as well as new large-scale installation works.

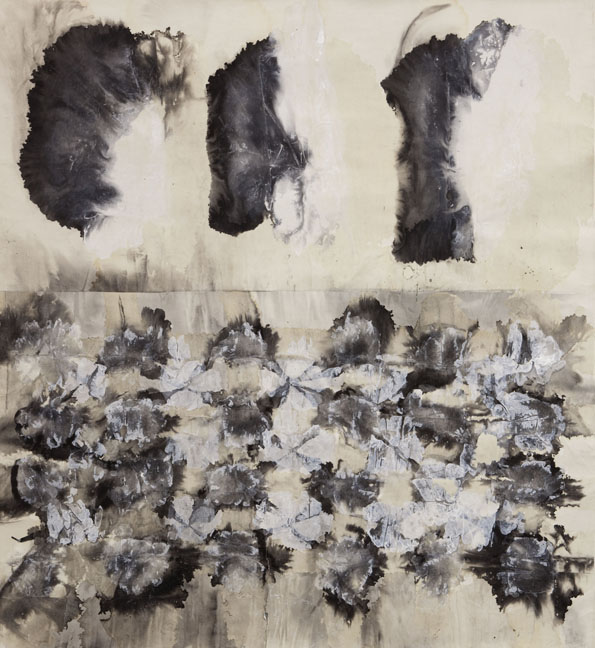

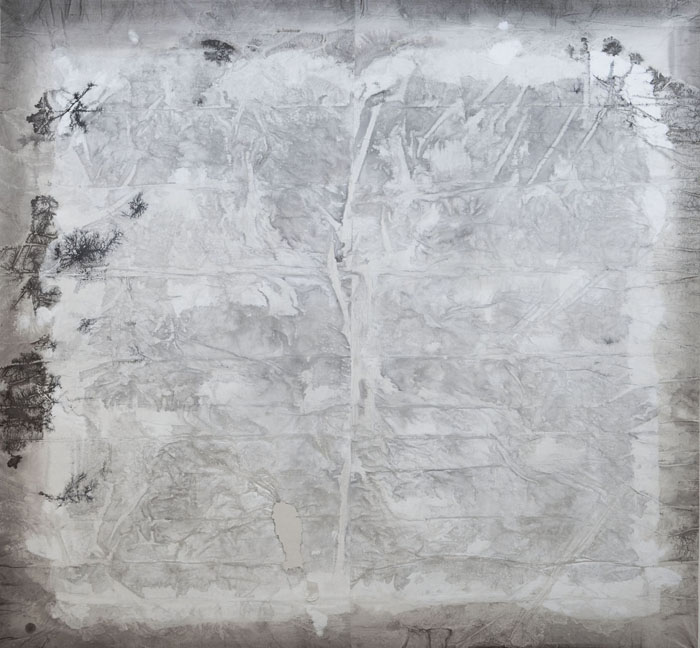

Zheng Chongbin is principally known for his large-scale ink paintings. For the past twenty-five years, Zheng has been exploring two issues that run throughout his oeuvre: firstly how to expand the potential of ink as a creative medium; and secondly how to incorporate new expressions of depth and structure into ink painting?

In his discourse, Zheng was to discover and in turn master the use of ink wash with acrylic and fixer. The relationship between the various media has led to the emergence

of a new visual language and the internationalism of ink painting.

With new modes of visual expression, Zheng has made works that convey heart-felt realities. He explores notions of self-value, existentialism as well as the practical and non-practical. Being a keen observer of human nature, Zheng’s works have often touched on the memories of human and animal forms – the unique characteristics of deformity, its existence and its various states.

Zheng’s monochromatic abstract compositions have often used familiar and unfamiliar shapes. He switches between existence and non-existence. In doing so he identifies imaginary spaces. Indeed, these spaces – or absences – become abstract and evocative forms.

The installation Encrustation is exhibited alongside Zheng’s ink paintings. Zheng is intrigued by the idea that significant parts of Southeast Asia’s heritage and culture are entombed deep beneath the sea as relics. Encrustation is a visual extension of historical symbolism from the re-creation of such objects. The work explores the relationship between archaeological artefacts and the art making process.

EMERGENT by Zheng Chongbin marks a significant departure for VWFA in showcasing

a work by a contemporary Chinese artist and for Zheng, it will also mark his first major exhibition in Southeast Asia.

New Innovations in Space: Paintings by Zheng Chongbin[i]

Britta Erickson

Zheng Chongbin’s recent series of paintings comes out of an extended gestation period during which he has both mastered his chosen media and arrived at a new understanding of space and structure. These works often hint at landscape or figural forms, but in the end they read as powerful abstractions. Zheng may not have consciously posed such a challenge for himself, but he has succeeded in creating a body of works that make a compelling case for the future internationalism of ink painting.

Enhancing Depth through Media Innovations

For over twenty years, Zheng Chongbin has been exploring two issues that mesh in his works: how can the possibilities of ink as a medium be extended, and how can a new expression of depth and structure be incorporated into ink painting? In 1986 he discovered a pair of materials that, in combination with ink, brought new visual interest as well as new technical possibilities to ink painting: white acrylic paint and fixer. When asked about his impetus to try these media, he replied:

Initially when I picked up the acrylic, I was thinking about it from the material point of view. I felt the painting physically did not have enough impact, and I wanted to add more textures as well as other layers beyond pure water and ink wash. My idea was to add one more element and then see what happens—explore the possibilities.[ii]

Basically Chinese ink painting is black and white—so pure. The two colors relate together in the working process. Ink can provide layers but the acrylic can create another layer of space that is completely different than the effect of ink and wash. . . . Traditionally all the sense of depth is created by nuances of how the paper absorbs the ink and to what extent people can see the paper itself through the ink. When you put the acrylic on that is another physical layer that you can play with so you have two physical layers, the paper and the acrylic, that can interact with the ink and give sensations of depth. . . . The acrylic works as both form and space. Using just ink you cannot achieve the same effects.

In addition to adopting unorthodox media, Zheng Chongbin has been using the paibi or broad brush in place of traditional brushes. He has found that using the broad brush changed his painting behavior:

. . . Ironically, the way I use the paibi is the same way I use the traditional brush, the same movements—in other words, although I imitated the traditional brushwork, I found it was interesting because the change in brush changed my behavior, the movements. The mix is interesting. But I never wanted to let go of the core things in Chinese painting, such as how to utilize space through your body gestures. . . . [And] in terms of understanding space, qiyun (spirit resonance) is essential.[iii]

There is one material aspect of painting for which Zheng Chongbin feels a kind of reverence: he uses traditional xuan paper made from bamboo fibers, and he prefers to use aged paper. He says:

To me the paper feels like it is in your blood. You almost feel you can taste it. Anyone who has done Chinese painting for a while understands that when you touch the paper, it feels like touching your skin. . . . Why not use cotton fiber based paper? It is completely different. Cotton cannot record each stroke you make. Bamboo does. It records one layer, a second layer, a third layer. And it gets even better as it ages. . . . New paper is so thin. As it gets older it feels like jade, it has a thickness—soft but with substance and body.

Education and Early Thinking

As a pre-teen, Zheng Chongbin settled upon figure painting as his chosen genre. Historically, landscape painting has afforded the ink painter more freedom than flower painting or figure painting: figure painting has always borne the constraining imperative to render the subject in a recognizable fashion. Zheng started painting when he was twelve, copying figures in lianhuanhua, or narrative picture books. He tested into the Shanghai Art Club as a young teenager, forming a subgroup with other young artists. They met to sketch models in each other’s homes, and the club provided lectures and demonstrations by teachers from the art school. In addition, Zheng’s parents engaged a private tutor, Mu Yilin (b. 1942), who in turn had studied with the great Shanghai scholar painters of the age, such as Xie Zhiliu (1910-1997) and Cheng Shifa (b. 1921): Zheng can thus claim a place in the long lineage of Chinese scholar painters. Mu Yilin took Zheng Chongbin to the Shanghai Museum, where he expounded on paintings in the collection one by one, explaining in detail the interrelated historical developments of painting materials, brushwork, composition, and so on. Chen Jialing (b. 1937), Zheng’s second teacher, had developed an innovative style by adapting the ideas of the great landscape painter, Lu Yanshao (1909-1993), to figure painting. He allowed Zheng to sit in on his classes at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Art.

Describing his training, Zheng says:

For us in figure painting, there was not much choice. In landscape painting, a rock or tree has no particular shape. The generalized form is most challenging for figure painting. We had to understand anatomy, and also there were formulas. We all learned how to render an eye by laying down one brush stroke, then picking up a certain amount of water and putting it down: it spreads out and forms the pupils. Similarly, we knew how to paint lips, and how to add other layers of color or light ink to bring everything together. It was so dogmatic! We learned the rules, and then tried to break away from them. That is how we trained. Our teachers were coming out of a very complicated situation. They wanted to make use of the expressive value of the line, so as to stay in keeping with Chinese painting theory. But on the other hand, Russian figure painting [which was highly influential during the Cultural Revolution and after] emphasized light and form, and influenced the understanding of the line.

In a way, it was an advantage that the study of figure painting required students to consider Western art more than did the study of other genres. They confronted a key issue that had occupied ink painters throughout the twentieth century: namely, how could an artist take advantage of a Western understanding of form and light, while staying true to Chinese painting? In class Zheng and his fellow students learned how to construct meaningful (figural) forms, but outside of class looked to Chinese art history to master the power of the line. For example, from the Chan Buddhist painter Liang Kai (c. 1140-c. 1210) they learned ways to render clothing expressive rather than purely representational; and from Chen Hongshou (1599-1652) could be gleaned ideas of how to convey psychological drama through taut and economical lines.

Conceptual and Compositional Depth

According to Zheng, while a student at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou (now called the China Academy of Art) he became interested in the surrealists and read Freud in his free time. The works of Salvador Dali (1904-1989) had a particularly strong impact on his work, suggesting new means of employing negative space, shadows, and dimensions—including psychological dimensions—all readily applicable to ink painting. Later, while teaching at his alma mater, Zheng painted a group of works on the borderline between figurative and abstract, using ink and acrylic on paper. Employing strong brushwork, he built up simple sculptural forms whose proportions are suggestive of human and/or animal figures. Their verticality encourages interpretation in terms of totemic symbolism, redolent with psychological overtones. Importing precepts of landscape painting or calligraphy he effected a transformation based in figure painting. Such transference of techniques or principles from one area of the arts into another has a long history in Chinese art as a technique for catalyzing transformative bursts of creativity. As an example of this Zheng mentioned, above, that his teacher Chen Jialing applied ideas gleaned from Lu Yanshao’s landscapes to figure painting. A century earlier, major figures of the Shanghai artistic lineage had transformed painting by adopting innovative calligraphic techniques as the basis of their painting.

Following his emigration to the United States in 1988, Zheng Chongbin focused for several years on conceptual and installation works. While installation undoubtedly represents a departure from ink painting, Zheng continued to work with issues and signifiers of long-term significance to his oeuvre, including ink and the relationship of the viewer to space. In 1999 he turned to pure abstraction with his Blot series, serene and impressive works whose innovative spatial effects hold the viewer’s attention. Subsequently, Zheng determined to develop more complex compositions with theatrical overtones: he has found inspiration in both early Chinese landscape compositions, and in Western contemporary and Baroque figure painters, as well as abstract expressionism. Again, the adaptation of forms and ideas from outside proved a dramatic catalyst for innovation.

Looking, for example, at Zheng’s 2010 painting, Raw, the influence of the monumental Chinese landscape painting tradition is apparent: the central vertical form is reminiscent of the monoliths dominating such paintings as the eleventh century Travelers among Mountains and Streams by Fan Kuan (late 10th-early 11th century). Raw’s convoluted formations also reference another eleventh century monumental masterpiece, Guo Xi’s (ca. 1020-1090) Early Spring (1072), whose interlocking, curving forms suggest the cycling of the life force, or qi throughout the landscape. In addition, in places the spidery bleeding of ink across the white acrylic mimics the crabby wintry trees of Early Spring. Beyond that, however, there is also the influence of Dali, Francis Bacon (1909-1992), and Caravaggio (1571-1610), all of whom presented the picture plane as a stage—a three-dimensional setting for that represented within the painting. Such conceptualizing of the picture plane can render the work highly dramatic. Clearly, the contorted forms depicted in Raw sit within a staged space, which thrusts them out of the picture plane toward the viewer; and the dramatic twisting of forms back and forth through space is heightened by Caravaggio-esque tenebrism (juxtaposition of extreme light and dark in figurative paintings, for heightened drama), a technique eminently suited to ink painting.

Dramatic tension characterizes Zheng’s recent paintings, whether their theatrical compositions appear to be framed or, alternatively, expanding indefinitely. Zheng says:

These are abstractions, but the forms are twined and twisted—there is a sense of tension. . . . Sometimes work can be very peaceful but this period has certain anxieties; it is very emotional. . . . Although there is a subject, it isn’t really clear as a subject, but it has a setting of actual physical space. That can help to enrich the forms. The forms may evolve, becoming flat or disappearing. This relates to Caravaggio: in his works [the eye is drawn] in and out of the space . . . it is very theatrical . . . everything moves. [Another influence is Bacon, in whose paintings forms] disappear in the background and emerge in the front.

Furthermore, many of Zheng’s paintings bear a conceptual link to the great early Chinese landscape painters, in that the painting presents but a segment of a conceived form. According to Zheng, “Fan Kuan, Guo Xi, and other Song landscape painters were working in a ritual way, not confined to the work itself, but expanding beyond. They never looked at the work as the work itself: it is only a segment. Abstract expressionism is the same, expanding beyond the picture plane. Also, the work is a stage of the ritual—it is not really work itself. When the work is done, the process is done, and that is the work itself. To me, to paint is like this.”

Conclusion

The idea of bringing together Caravaggio and Fan Kuan, Bacon and Guo Xi seems highly improbable, and yet Zheng Chongbin has synthesized essential qualities of these disparate giants. The quiet power in the resulting works is tensely contained: most obviously this is due to their structure. But underlying the compositional tension lies the potentially explosive fact that these works have created a new space for Chinese art—both a new kind of pictorial space, and an art historical space carved out by Zheng’s unprecedented and profound approach to the synthesis of East and West. He has opened a door whose existence was hitherto unsuspected.

[i] This text is based on my earlier essay,” Innovations in Space: Ink Paintings by Zheng Chongbin,” in Chongbin Zheng: Ink Painting (n.p., 2007), pp. 28-31.

[ii] All artist quotes are from an interview between the author and the artist, conducted in the artist’s studio in San Francisco, 20 October 2006.

[iii] Interestingly, Zheng went on to say that he also uses the concept of qiyun to understand contemporary art. It provides “a different angle from which to approach it, although the history behind it is completely different. . . . There is a very similar conception of space between Western painting, especially contemporary work, and old masters, as compared to Chinese paintings.”

* * * * * * *

Connecting The Real and The Fake – Zheng Chongbin’s new work

Hou Hanru

Zheng Chongbin is known for his engagement with ink-wash painting for the last decades. However, his new project for his one person exhibition in Singapore, to the surprise of those who are familiar with his art work, is a large scale installation called “Encrustation”. Taking over the entire main room of the gallery, this sculpture-based installation consists of various elements that represent symbols of Singapore’s identity and historical past. It’s large and monumental. At the same time, it’s also dynamic and open to different readings and associations: seven ceramic reliefs of lion heads mounted onto the surrounding walls while one full-body sculpture of the lion is crouching on the floor. In the centre, a huge tree trunk with scars and encrusted with broken ceramic plates is hung from the ceiling to form the focal point of the whole environment. Immense, heavy and potentially swinging in the space, it appears to be at once attractive and treacherous, like a kind of mystic meteorite falling from outer space, awaiting attentive scrutiny and identification. It invites archaeological explorations. Together with the estrange combinations of the emblem-like reliefs of lion heads and realistic but fossil-like sculpture of the lion, it forms an intriguing site of excavation…

Indeed, Zheng Chongbin himself states the intention of the project as centred on “archaeology”. Originally naming the project “Object of Great Reality”, his idea comes from his conversation with Valentine Willie, the gallery owner who invited him to do the show, about “how South Pacific Asia Culture was formed, and I learned that this great area has long connection to its archaeology”.[1] Immediately, the artist was fascinated by the historical connection between the formation of the region’s cultural identity and the trade of ceramics. Here he discovered a particular connection with his own Chinese heritage. “The ceramic object is (made and through predominately Chinese exporting) from the 11th to the 19th century. Through the Chinese maritime merchants to venture beyond their shores to trade with South Pacific countries, it became the key means by which the heritage in the region was formed. As The New Straits Times pointed out: the past is what is submerged in the surrounding seas, rather than the terrestrial heritage. This really triggered me to want to formulate my visual interpretation as a gesture in the direction of their archaeological in relation to the art.”[2] Zheng Chongbin goes further to manifest that the project “is about reassessment. The reassessment of an object represents a great luxury… What interests me most is that our time is always in coexistence with our surroundings, which remind us (of) where we have come from and what we have become. The past global colonialism through its trade, cultural and commercial demands continues to be the means today for us to identify ourselves. I wanted to create a field through the work that suggests the meaning of mass production, repetition, exportation, deterioration and identification. The view moving through this work what we are living through. That is the perspective I want the viewers to connect with.”[3]

Finally, the artist reveals: “Art is illusory, not only visually but mentally as well. Art can get its way by making something which often deceives, for us to understand our environment in much better way. The real and the fake are not so important to the art: what’s important is to connect the real and the fake. The success of making the connection is what makes art possible.”[4]

Now, the title of the project from the original “Object of Great Reality” has been changed into “Encrustation”. It’s clearly a relevant and efficient decision. The original title suggests a comprehensive and totalising view of a vision of a cultural identity, or even a history. By shifting it to a much less generic and monolithic direction to embrace “encrustation”, or collage of diversified and fragmented elements related to the presumed image of the cultural identity, the artist is presenting the real function and significance of archaeology, where sit both its power and limit. Here, archaeology, appropriated in the making of an art work which is beyond the domain of the “scientific”, implies an ongoing negotiation between research of historical facts and artistic imagination, between reality and fiction. What is the most significant is the energy and creativity generated in this endless process of wrestling with the “heritage” and opening towards possibilities of new interpretations. These new interpretations serve to reveal new ways for us to continue to redefine our own identities and our relationships with “reality”, that is also in eternal remaking.

Therefore, the artist has decided to render the installation into a series of elements coexisting in a rather unlikely and uncanny way – the coexistence of a trunk with encrusted ceramic plates and two forms of representations of lion in 2 and 3 dimensions. Resembling a part of a sunken ship transporting ceramics (from China, probably), the trunk, suspending in a precarious equilibrium, provokes doubts about its authenticity. This suggests, more or less obviously, a question about the origin of the cultural heritage that it represents in spite of the popular assumption of its “Chinese-ness”. What is even more suspicious is the images of the lion, swinging between two competing forms of representation – relief and full-volume sculpture as if one claims more “reality” than the other…

Here, one must remember that this specific work by Zheng Chongbin has been a result of his “sudden” interest in Singapore and its cultural identity due to his decision to respond to the invitation to hold an exhibition in this city-state. For the last months, he has become a frequent visitor to the city to create a public art work commissioned by a real estate developer, next to well-known artists like Anthony Gormley and Sol Lewitt. He has developed a project consisting large ceramic pots to form up a jungle-like garden for the site and the atrium of the building. As an artist of Chinese origin living in San Francisco for more than two decades, Zheng Chongbin has also been involved with designing ceramic tea wares along with his ink wash painting creation. If the reference to ceramic trade was to explore that “natural relationship” between himself as a “carrier of Chinese heritage”, the image of the lion would bring us directly to the contemporary reality of this locality. Historically, the route of ceramics, the major maritime trade between China and South Pacific regions, has played a fundamental role in the formation of the Singaporean society. What is even more critical and decisive, however, is the multi-ethnical and multi-cultural dimension of the Singaporean society. The formation, maintenance and continuation of this complex “collage” of different communities and their values are essentially relying on a certain common efforts of union, or consensus among them. This force of union has been based on resistances against foreign domination and struggles for independence in different periods of history. This national union in its contemporary form is actually extremely recent and somehow artificial. It tends to erase as much as possible contradictory and dissident voices. And, ultimately, along with the pragmatic solution resorting to economic development that the city-state has largely succeeded, it needs a highly articulated and somehow simplified symbol as a kind of “fetish” to manifest and consolidate its legitimacy and new-born identity. In other words, it needs to come up with a myth of the Nation. The legend of Singapura in Malay tradition, or the Lion City, has hence become the very emblem of such a symbolism. What is particularly interesting is, after all, this country has been made up of immigrants from different parts of the world – mainly the pacific regions, from China to India. In a way, the union of the nation, more than often, has to face challenges of diverse claims from different communities. This makes the image of the lion even more crucial to the survival of the nation. Purportedly displaying two possibilities of rending the lion in two imagery systems that can evoke diverse and divisive effects on the understanding between the symbol and reality, Zheng Chongbin, indeed, brings the audience to a re-examination of the real nature of this union itself… in an aesthetically pleasant but somehow intellectually awkward way. Certainly, this points to the very nature of archaeology itself, especially in the sense of archaeology of knowledge, as not only a process of verification of historic hypothesis but also revelation of how social, political and intellectual power structures have been fabricated in this process of “verification”. In turn, these very power structures have manipulated the production of “reality”, as Michel Foucault may emphasize.

Ironically, according to scientific archaeology, lions have never been living in the area where now Singapore stands. Instead, it’s probable that a kind of Asian tiger was living here before the land was explored by human beings. The earlier settlements, until the island was occupied and colonised by the British, were mainly fishing villages.[5] Nevertheless, the very image of the lion has been officially affirmed as the nation’s symbol. Of course, this is by no means the unique case of Singapore. Numerous similar stories can be found across the world, in countries seeking unifying strategies to establish the geopolitical structure of modern nation states – just look at how Chinese are debating on the choices between dragon and panda as their national symbol! Provoking some suspicions and questions about the commonly accepted national symbols can certainly help us understand better the formation of reality in which we live, especially in terms of how the relationship between individual and society has been defined. What’s even more important is that this can encourage us to investigate more deeply issues related to imagination, creativity and freedom against the domination of social consensus. Artists are certainly working on the frontline of such a battle. Enquiring and even challenging all kinds of social, cultural and political clichés are integrate missions of art, especially in the contemporary context when our society is facing the task of negotiating its place in the globalisation process. This critical re-examination of the formation of “reality” becomes even more urgent when Singapore and Asian Pacific Region at large, thanks to the “economic miracles” they have achieved, are becoming a major player in the current restructuring of global economy. The question is: what kind of miracle is this?

Here, I’m reminded of a true story: the Singaporean artist Lim Tzay-Chuen was selected to represent Singapore in the 2005 Venice Biennale. His project was simply displace the famous “Merlion” statue by Lim Nang Seng under the commission of the National Tourism Board – a revised version of the mythic lion – to Venice. This displacement seems to be a great gesture to promote the nation’s glory in the most privileged international art event. However, the artist was more interested in how people react to the empty space left behind by the temporary absence of the monument. The “spokesperson of the artist” explained:

“Tzay-Chuen finds the fact that the statue is missing more interesting than its appearance in Venice. He thinks its disappearance offers a unique opportunity for Singaporeans to rethink and reinvent the story of the Merlion. When Mr. Lim conceived the Merlion project, he imagined children having their pictures taken at the empty site, and years later, showing their own children that they were there when the Merlion went on a holiday/adventure. There are few national icons that will have such an interesting life – travelling to Venice and participating in the world’s oldest international art event.”

“A big welcome ceremony is being planned when the statue returns at the end of the year. Seven-year old Mike Goh, from Saint Stephen’s Primary School, said, ‘I really miss the Merlion, I can’t wait till it comes home.” [6]

Perhaps, Zheng Chongbin’s project can be seen as an echo to this radically provocative project. Out of the ruin of cultural heritages, the Lion is back. It never really existed. But, it’s SO present! We should be reminded of the artist’s claim: “The real and the fake are not so important to the art: what’s important is to connect the real and the fake.”

1 March 2010, San Francisco

[1] Zheng Chongbin : notes on the project. 2010, Unpublished.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ref . Wikipedia, among other references on Singapore’s history.

[6] Appendix, Proposal by Lim Tzay-Chuen, 28 Feb. 2005, The News Times: Singapore Icon makes a splash at Venice Biennale, June 9, 2005, by Cindy Vogel. In “Mike”, Lim Tzay-Chuen, Singapore, 51. International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia; National Arts Council and Singapore Art Museum. p. 35