Jonathan Ching

Days of Thunder

Valentine Willie Fine Art is delighted to present Jonathan Ching’s first solo exhibition in Kuala Lumpur – Days of Thunder. This new body of work is marked by the artist’s fascination with both the immortality of youth and entropy as conflicting forces, that is embodied in popular culture.

Drawing from well-known media references, Jonathan delves into the question of expiry – whether a star personality or a cult figure knows when to quit. By depicting once powerful figures in popular media such as Muhammad Ali as an old man, a retired Lone Ranger sitting forlornly in a suburban living room, a ruined statue of Ferdinand Marcos, the artist also describes how energy (or the vitality of youth) is not destroyed in most cases, but drives on.

These lyrical images convey a balanced portrait of human strength and frailty, revealing the sad irony behind our youthful aspiration, tinged by an element of pathos. Days of Thunder underscores Jonathan Ching’s mastery of the oil paint as a poetic medium to express the poignancy of our human achievements and loss.

Interminable Youth

Immortality is the only thing which doesn’t tolerate being postponed. – Karl Kraus

Immediate,expansive, forceful, urgent, ageless, indestructible. These are some of the qualities we turn to describe immortality. The idea of the eternal and the everlasting rests on a state of being that renders time irrelevant. So how could immortality, as Kraus has put it so well, be postponed? Days of Thunder, a new series of paintings by Jonathan Ching, is marked by the artist’s fascination with both the immortality of youth and entropy as conflicting forces that are embodied in popular culture and by extension, personal history. Drawing from well-known media references, Jonathan delves into the question of expiry – whether a star personality or a cult figure knows when to quit. By depicting once powerful figures in popular media such as Muhammad Ali as an old man, a retired Lone Ranger sitting forlornly in a suburban living room, a ruined statue of Ferdinand Marcos, the artist also describes how energy (or the vitality of youth) is not destroyed in most cases, but drives on.

Ching’s broad and loose painterly strokes differentiate his paintings from that of photo-realism. This conscious move enables him to create an effect of ephemerality, shaping a surface arrangement that doesn’t quite hold together an image too tightly. They cohere in the moment they are summoned on the canvas, but are always hinting at its dissolution, as if they are fully aware of their temporality. Through this formal deployment, Ching is able to weave his personal history into a history of the images that reflect the staying power of the media icon.

The series convey a balanced portrait of human strength and frailty, revealing the sad irony behind our youthful aspiration. One is led to believe in the belatedness of the painted subjects, that they have past their prime. What is strangely beautiful is the pathos that is revealed by his subjects holding tightly onto pieces of this enduring past, unwilling to let go.

The diptychs, through which Ching is able to juxtapose two images alongside with the introduction of texts into his paintings, make up the first half of the exhibition. On a whole, these works chart the artist’s thematic interest on an epical scale, drawing on the history of politics, sport and culture, and addressing how the media spectacle is complicit in the replication of immortality’s mythic resonance.

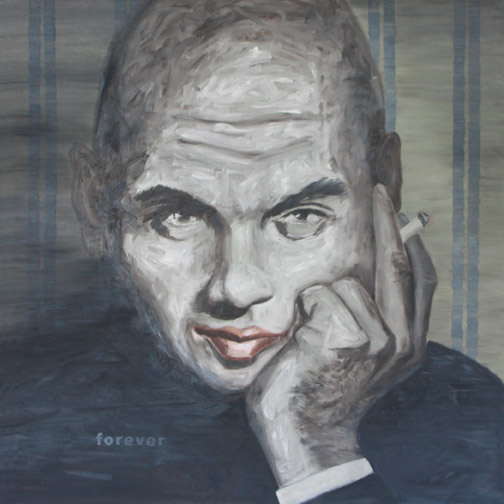

In Maybe Mortality Is Just A Matter of Remembrance, Ching offers to us two stubborn images of former president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos that argues for his continuous relevance in spite of his political defeat and ultimate vilification. One panel depicts the ruined concrete giant bust of Marcos on Mt. Pugo, while the other panel shows Marcos with a cigarette in hand, emphasised by the words, I want more life, Fuckers!

This juxtaposition pits a wrecked monument of Marcos against a portrait of his that demands for more life. The destruction of a monument, which is symbolic of the everlasting icon, coupled with a figure who demands for more life even as he is a smoker and therefore more prone to succumbing to cancerous diseases, are not only ironic statements, they stand for the contradictions in a political will, using the metaphor of the life-wanting smoker to underscore the Marcos’s self-incurred downfall.

In Days of Thunder, Ching’s fascination with daredevil motorcycle stuntman Evel Knieval takes on a nostalgic turn. This diptych suggests the culture of risk-taking as a physical trial through which a more authentic recognition of what life is can be redeemed through a close encounter with death. One panel describes wrecked cars arranged to form a modern day Stonehenge. By hinting at the form of an ancient monument, Ching suggestively translates the success of Evel’s bold, courageous, though not necessarily rational convictions into stuffs of perennial legend. In the pendent painting, Evel’s portrait speaks to us in the following words, Viva La Vida, lending weight and meaning to what it means to be alive through an act that repeatedly confronts existential values at the threshold of death.

We Were Immortals series comprised of four smaller portraits through which we encounter four personalities balanced between the iconic and the personal. The titles of these works conveys no small amount of frustration, as if the subjects themselves lack the recognition that was once accorded to them.

In I Was Always The Action Hero, we see the figure of the lone ranger, sitting forlornly in the living room accompanied by an action figure depicting his action hero days, clinging on to a belief in his staying power. Likewise I Was The Greatest illustrates Mohammad Ali’s unfazed stare that challenges us to recognise his supremacy as a fighter. While these two icons of the twentieth century represent the brazen machismo that defined modern masculinity, they now face the threat of time that erases them on both counts – in popular imagination as well as their physical strength.

Two other portraits in belonging to We Were Immortals are personal in nature. Ching paints his father in one of them with an assurance that the image also bears a fading trace of an impression a child has towards his or her parents. Recognising his father at this stage in life, one realizes that kind of immortal power that a child once believe in a parental authority is now loss. The father is no longer an immortal being but one that is equally human.

Finally, in a quiet and elusive self portrait, a present day Ching stares out at us, recoding the present and intimating at a past that seemed much more halcyon. In a short anecdote, the artist describes how he remembers being a kid and having the ability to jump down a flight of stairs. Back then, there was a feeling that one was imbued with the physical prowess that allowed one to do anything one wished to do. With age, that feeling of invincibility is no longer present. But the memory of this conviction abides and finds its way to draw out this history of struggle, against time, to return to an irredeemable state, when one once believed that one could take on the entire world.