Yogie Ginanjar

Versimilitude

Returning to KL after his successful VWFA Project Room exhibition Neo-Chiaroscuro in 2009 VWFA KL is pleased to present Verisimilitude the first major solo exhibition in Malaysia by Indonesian artist Yogie Ginanjar. The title of the exhibition uses the term ‘verisimilitude’ or versions of the truth as found in literature and the visual arts. It is this notion of recreation that resonates within the artist’s practice as he attempts to highlight its artificiality and the hierarchy of images within the practice of pop culture and contemporary art.

Developing his ongoing interrogation of iconic works from Western Old Master painting and the critical collaging of ephemeral photographic images from the Internet, Ginanjar looks at processes of reproduction and ideologies of identity. Throughout the show audiences will recognise images from the canon of Art History as they attempt to decipher his hybrid iconographies. By destabilising and parodying the familiar he questions the status of painting as well as the complex relationship between East, West and global sensibilities.

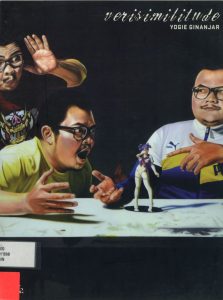

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Otaku develops the Ginanjar’s fusing and questioning of visual influences where the artist paints his friend and local artist in multiple versions as the characters in Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicholaes Tulp. However the object of interest is not a human cadaver as in the original but a Japanese anime doll as part of the fanatical Otaku culture that idolises fictional comic and animated characters. This humorous objectification fuses the dramatic strategies of lighting and composition taken from historical painting with contemporary pop culture and irony.

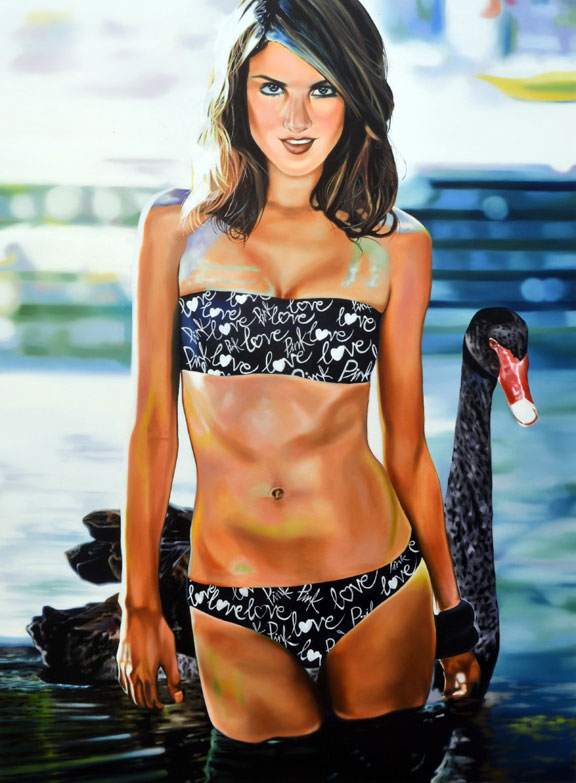

The Big Catch with the Fall of Icarus continues his fascination with the mythical Greek story of the boy who tried to escape imprisonment by flying away from captivity using wings made of wax and feathers, but who, in his excitement flew too close to the sun, melting his wings causing him to tragically plummet to the earth. As in previous works on this subject, the artist inserts the moment of the fall into paintings of sampled Internet images of Caucasian subjects on holiday. This objectification of his subject, stripped of all individuality, puts Ginanjar in a position of power as he creates a farcical statement about decadence, artificiality and personal questions about Western dominance that slowly corrupts and absorbs local contexts.

Truth in Illusion

By Eva McGovern

Yogie Ginanjar enjoys paradox. His practice is a careful blend of critique and irreverence, anxiety and amusement. It is a necessary strategy that seamlessly combines his eclectic interests in post-colonial theory, art history, pop culture and kitsch. This mixture of in-depth analysis and superficial pleasure fuels academic and iconoclastic conversations about identity and the impact of Western art history in his own context of Bandung, Indonesia. Rejecting didactic statements, he instead contributes a rich polemic filled with contradiction. Such opposing forces are indicative of a generation eager to mine from the past in order to blur the boundaries between high art, identity, appropriation and entertainment. The title of the exhibition uses the term verisimilitude, or versions of reality found in literature and the visual arts, as an entry point into Ginanjar’s vision. It is this notion of observation and recreation that resonates within the artist’s practice as he attempts to highlight the illusion of fixed assumptions in art and identity. As such, he continues his fascination with contemporary restagings of European Old Master paintings and the objectification of Caucasion subjects on holiday. Focusing on notions of the gaze, and the artist-subject relationship, the outcome is a curious unravelling of the complex relationship between East, West and global sensibilities.

As an academically minded painter, Yogie Ginanjar has been seduced by the emotional gravitas found in European art from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries. The technical skill and sensitive handling by Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Velasquez still remains a significant point of technical learning for many artists today. Studying their masterful employment of figuration, lighting, texture, and composition, Ginanjar respectfully simulates this heightened theatre of emotion in his own hyperrealist, superflat style of painting. However, by removing the intricacies of symbolic detail common in classical painting, the artist isolates and amplifies his human subjects against an inky darkness to create a focused approach to subject. Importantly, rather than a straightforward reproduction, he uses the technical concepts from the original to create a dramatic parody that shifts meaning and perspective from Western to Eastern centres. Although his figures mimic the poses of their European predecessors, his local Indonesian subjects, which include the artist himself, purposefully sets into a motion a playful game of identity subversion.

The Marriage is a reconstruction of 15th century Dutch painter Jan van Eyck’s now iconic The Arnolfini Portrait from 1434. The original is a double portrait of a wealthy Italian businessman and his wife. Filled with symbolic details of love, marriage and gender roles, the work has been praised for its highly realistic rendering of texture, costumes and convincing depiction of an interior setting indicative of the culture at the time. Ginanjar’s The Marriage recontextualises the theme of Van Eyck’s work into a contemporary version looking at the performance of gender. His figures stand holding hands in the same posturing as the Dutch Master’s work, however their clothing; highly stylised and camp, is not a realistic portrayal of couples in Indonesia but a staged commentary that reveals an atypical approach to men and women. As society has evolved, the unconventional aspects of sexuality have become more visible and acceptable. By choosing androgynous figures, he presents the feminine and masculine sides of both sexes, who are more confident to go against convention and express their individuality. Their exaggerated appearance: spandex gold trousers, red boots, cowboy hats and wigs reminds one of a fashion shoot, hinting at Ginanjar’s process of assembling a cast of characters manipulated by the artist during a labour intensive photo shoot to create the exact image to paint from. His statement on sexuality, although based on observation, is nevertheless a constructed ‘truth’ amplified by his fusion of reality and imagination.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Otaku develops Ginanjar’s dramatized truths through yet another articulated setting, where the artist paints his friend; local artist Radi, in multiple versions of the characters in Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicholaes Tulp, from 1632. However the object of interest is not a human cadaver as in the original, but an anime doll as a representation of the fanatical Japanese Otaku culture that idolises fictional comic and animated characters. This humorous and sexualised female objectification fuses the dramatic strategies of historical painting with contemporary pop culture and irony. By once again subverting the subjects of his Old Master originals with sub and pop cultural signifiers, Ginanjar canonises his peers and youth culture into the fabric of historical painting to breath new perspectives into the vaults of traditional art history.

Although iconoclastic, Ginanjar’s works are not bastardisations of Old Master work nor a form of cultural anthropology. Rather, it is the absorption of skilful painting with a different set of signs, symbols and meanings. This then becomes part of the artist’s conversation with and provocation of established ideas within art and society regarding the subjugation of the ‘Eastern’ viewpoint and position. When discussing his work he comments:

With parody and eclecticism as my language, I disturb and interfere with various established codes amongst Western classical paintings. The reason for this creative process is my personal statement towards a tendentious history within Post-Colonial discourse. At this stage, though I am aware that it is a utopian goal, my aim is to create an Occidentalism, in a sense of “vengeance,”

By reconfiguring his understanding of Western positions, structures and concepts he attempts to contribute an informed perspective that is inspired but not limited by Edward Said’s (1935-2003) concept of Orientalism from the literary theorist’s now iconic book of the same name published in 1978. Locating himself within this post-colonial discourse, Ginanjar relates to Said’s observation that the East was purposefully denied its own voice, because of subjugating viewpoints during the Colonial period. This justified the need for Western control and dominance on its colonies who were deemed passively exotic and therefore ‘unable’ to self govern. What resulted was an enduring perception through literature and visual media of the West as author of ‘the Other’ or the East. Although Post Colonialism, pluralism and the rise of global economies has upset this hegemony, hundreds and hundreds of years of colonial rule has meant this type of reductive essentialising still occurs today, conspicuous by how developing countries ironically aspire to a more Western sense of generic global modernity. The term Occidentalism then emerged as the inverse of Orientalism, communicating the opinions of the ‘Occident’ who has discarded the term Oriental, in a gesture of self awareness, to observe and critique their Western counterparts. Ginanjar’s Occidentalism or, ‘revenge’ as he declares, is therefore a two-fold theatre of the absurd about the dilemma of art and identity, based around the gaze between subject and object, and the control of identity.

It has been accepted, that the concept of Art, from a historical perspective and in contemporary understanding, has evolved from the West. Art created outside of the West, therefore, appears to be dependent on Western signifiers for validity. As the Occident, Ginanjar presents his awareness of an artist taught to understand his craft based upon Western histories, but who also wants to complicate this situation through active observation and inquiry. This seizure of control gives him the power to define or complicate his subject matter and, himself. His disturbances are not provocations as such, since it is clear the artist does not subscribe to binary oppositions and protest. But rather, this position of power allows him to rupture the authority of history to reclaim his own identity. This identity is not however, based upon a desire to promote a specific idea of Indonesian culture and art. Rather Ginanjar is part of a generation that subscribes to a global community based upon a system of capitalism that now defines us rather than clear notions of East and West.

His images of Caucasian subjects on holiday present a different approach to his Occidental revisioning. Sourcing images from the internet, Ginanjar presents ephemeral photographs of nameless individuals enjoying various recreational activities from fishing to time spent at the beach, juxtaposed with visual or textual motifs from Greek mythology. The Big Catch with the Fall of Icarus continues his fascination with the Greek myth of Icarus, the boy who tried to escape imprisonment by flying away from captivity using wings made of wax and feathers, but who in his excitement, flew too close to the sun, melting his wings and causing him to tragically plummet to earth. Taking place characteristically in the background, the foreground is filled by a man holding a large fish caught on holiday, a trophy of his success. The symbolic fall, as in other works such as Leisure on the Grass with the Fall of Icarrus therefore, emphasises an absurdity about the subject, unaware of their own mockery. This reduction of his subject, stripped of all individuality, puts Ginanjar in a position of power as he creates a farcical statement about decadence, artificiality and the dominance of Western culture in an international world.

It is important that these figures are strangers, with no relationship to the artist whatsoever. Instead, they are reduced to mere objects ‘stolen’ from the Internet, manipulated by another form of voyeurism. Rather than contemplating on his own image or those of his Indonesian contemporaries within the canon of art history, Ginanjar in this instance objectifies his subjects to present a bias statement of ridicule or point of curiosity as the West has done to the East for so long. Once again it is a reversal of power structures to create a slanted viewpoint that reveals more about the artist himself than his protagonists. This is his attempt at a type of personal portraiture, where Ginanjar, although invisible, becomes the subject of his own work. His depiction of media driven female exploitation through the erotic bikini clad Caucasian Leda, and his confrontationally strong Indonesian Danae, reveal the desires, confusion and frustration of an individual coming to terms with his own interests and views on the world.

The truth that Ginajar ultimately reveals in Verisimilitude is that reality is now based on illusions and simulations of lived experience. The nature of reproduction and appropriation then, is the final aspect of Ginanjar’s observations in his exhibition at Valentine Willie Fine Art. Figurative painting as a medium is a memetic art based upon an original found in real life. It is a verisimilitude or semblance of the truth but not truth itself. Contemporary realist painting has also introduced another mimesis; photography, in its process of reproduction, further distancing its proximity to the real. The original is flattened through the photographic mode to become a surface for painters to imitate onto canvas. Ginanjar’s use of books to select his Old Master works from or the Internet to steal his photographs, create a further detachment from the original since these too are simulations. The abundance of these ‘false sources’ demonstrate French theorist Jean Baudrillard’s (1929 – 2007) concepts of simulacra and simulation which discusses that the real is now but a simulation of itself, and that our reality is based on artifice whose true origins are being forgotten in favour of a more slick hyper real versions of itself. Therefore, life has become its own mimetic art form experienced through the media and second hand sources such as television and the Arts rather than real life experiences. This death of the real is the ultimate sacrifice for our love of information and exaggeration. What is left behind are the signs, symbols and codes of the real which, is the new ‘truth’ of the contemporary condition. This is the fall, the seduction and the allegorical exploitations to be found in Ginanjar’s work.

The lament of the real through a visual hijacking of art history is the tension found beneath the surface of Yogie Ginanjar’s sensual, playful and hyper realistic work. By revealing the universal problem of identity; audiences see an artist and individual searching for answers and meaning amongst the numerous signs and symbols that bombard society through the media and modes of capitalism. However, underlying his academicism is a straightforward desire to prove his skill as a painter through the depiction of lighting, figuration and realism to create emotional drama. Audiences can choose to simply enjoy his mastery of form and surface or join the artist on their own journeys of self-introspection to reveal the myths, illusions and truths regarding our positions as Southeast Asians in the global world.