Vasan Sitthiket

Vasan’s Women

Valentine Willie Fine Art is delighted to present Vasan Sitthiket’s second solo collaboration with Valentine Willie Fine Art entitled ‘Vasan’s Women’.

Women in various guises occupy a special place in Vasan Sitthiket’s oeuvre. Pictured alternately as either passive objects or active and powerful players shaping their own destiny, Vasan’s women are variously depicted as purveyors of sexual temptation, victims of the sex trade, complacent subjects of consumer-targeting propaganda, maternal givers of life, and metaphorical icons assimilated with mother-earth-mother-Thailand. Often viewed with tenderness and admiration by the artist, whether portrayed as young or old, whether shown as agents for good or evil, Vasan’s take on the opposite sex is personal and heart-felt rather than generic.

This exhibition is curated by Singapore-based, Iola Lenzi. She aims to look at Thai society through the prism of women as portrayed by Vasan Sitthiket. The women of Vasan’s paintings and 3-D works, examined as a whole, embody a complete universe reflecting the layered complexity and many contradictions of Thailand and indeed the region today. In an oblique manner, Vasan’s Women also endeavors to visually document the nuanced and distinct position and role of Southeast Asian women within wider Asia. Comprising over a dozen new works of painting and sculpture produced specifically for the present exhibition.

The examination of our pre-modern past yields the discovery that the women of Southeast Asia have not shared the same grim fate as their sisters in China and India. In many parts of the region, women’s role as child-bearers traditionally afforded them a special status unavailable to men(1). Not only did fertility ensure society’s regard, the process of gestation often played a part in its belief in women’s magical and ritual powers. And though in pre-modern times Southeast Asian women could not be said to enjoy equality with men because the two sexes seldom competed directly in a single sphere, women were more respected in society than their peers in North and South Asia, were not infrequently relatively autonomous, and were sometimes known to play important roles in local economic life(2). The erosion of the conception of woman as social participant rather than oppressed chattel is a relatively recent development in many parts of Southeast Asia, linked to colonialism, changing interpretations of religious precepts, the birth of modernity, urbanism, and regional economic inequalities(3).

The ancient matrilineal tradition of the Malay world, elements of which have survived in some form even since the Islamisation of the Malay peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago, has contributed in no small part to women’s relative strength in insular Southeast Asia as well as swathes of the mainland that are now Malaysia and Southern Thailand. The continuing influence of old but sometimes resilient vestiges of animistic belief(4), and the syncretism pervasive in the region until now, also go some way to explaining our women’s complicated social balancing-act today.

In some countries -notably Singapore where a significant indigenous female population only burgeoned in the 20th century- contemporary feminist discourse is linked directly with the 20th century development of Western gender politics. However in many other locales, including Thailand, the feminist cause in its contemporary incarnation finds its roots in a more diverse set of parameters. These, though related primarily to wider social emancipation(5) brought about by 20th century socio-political changes, are also tied to ancient customs, the origins of which reach far back into the annals of regional history.

In Vasan’s Women, Thai painter and inter disciplinary artist Vasan Sitthiket sets out to unravel the numerous and often contradictory strands of fact, belief and assumption revolving around the idea of woman in our part of the world. His expressive vision relates directly to the Thai situation, and indeed more specifically to his own perception of woman, as gleaned from personal experience growing up in the changing but still very socially conservative Thailand of the 1960’s and 1970’s. Vasan’s approach to the theme, tackled systematically for the first time by the artist in this project, is, however, far from monolithic. Moving from the intimacy of his portraits of his mother and grandmother, to the social commentary of his evocation of the generic woman labourer set against the contemporary glitz of a Southeast Asian urban skyline, to images of mother as quintessential progenitor of civilisation with all its ills, to the young urban consumer-girl, through paint, mixed media, and canvas the artist conveys his empathy and love for women, as well as his critique of their place –imposed or espoused- in today’s society.

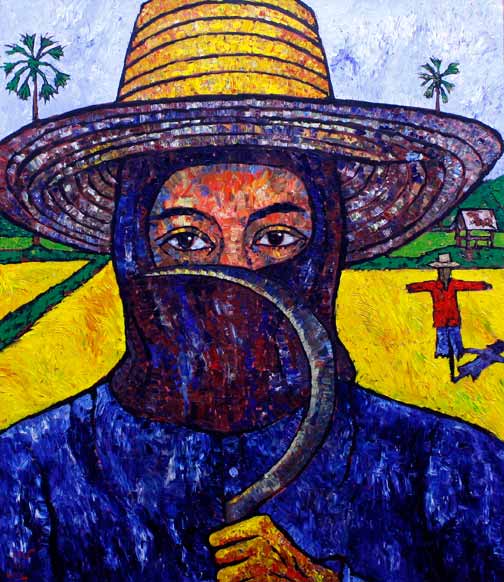

This body of new work is as variegated in artistic and conceptual reach as the complex question of women in Southeast Asia itself. Paintings such as Female Labour and Female Farmer, using coldly precise brush strokes and a hard, frank, gleamingly colourful palette, through form as well as iconography, aptly articulate a specifically regional dichotomy. Here Vasan, by setting the semi-obscured, nearly featureless faces of women workers against, in one case, a glossy cityscape backdrop, and in another, a tract of farmland, highlights the paradox of the inequitable interdependence that exists in developing Southeast Asia. Without resorting to slogan or manifesto, these paintings speak eloquently of the contrast between the financial and political elites -owners of the slick, first-world city-centres and the modern farms, consolidated through expropriation-, and the impoverished interchangeable laborers who, from either the country’s own third-world rural backwaters, or poorer regional neighbors, are the ones actually building the cities and tilling the land. Vasan might easily have inserted men, rather than women, into his urban and rural settings. His choice of women makes these two paintings all the more poignant for their juxtaposition of female physical vulnerability with the women’s uncomplaining shouldering of the weight of regional prosperity. Female Labour and Female Farmer, though narrating accepted exploitation, also underscore women’s significant contribution to Southeast Asian modernity. With these two canvases Vasan Sitthiket probes some of the region’s most contradictory and challenging social and economic realities.

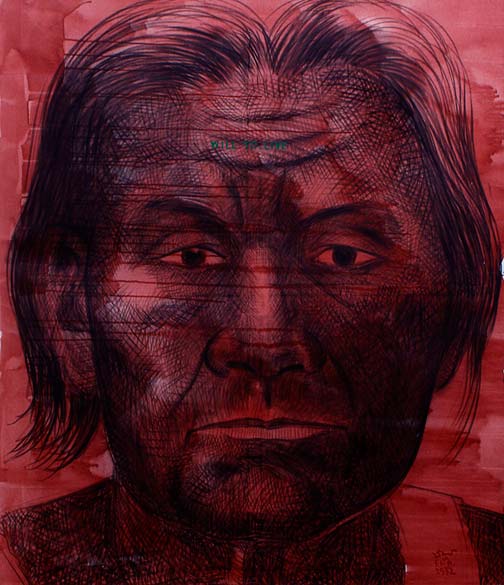

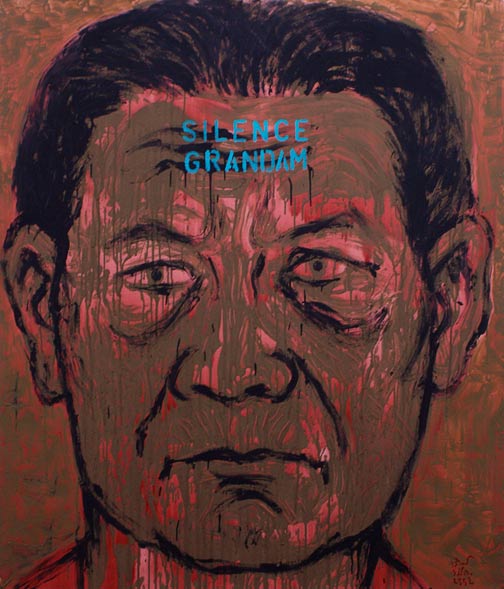

Quite different in tone and pictorial approach, are the artist’s portraits of his grandmother and mother. Harking back to the giant 1998 paired graphite on paper images of grandfather Sangasa and grandmother Sangasi(6), Silence Grandam and particularly Artist’s Mother are sensitively rendered, their classical formal language belying their vigour and subtly contained but very real emotional charge. Artist’s Mother is executed in crayon on canvas, and tersely spontaneous, possesses the immediacy and directness characteristic of drawing. Though neither woman is physically idealized, such is the intensity of feeling and memory in these depictions that one gets the sense of the artist’s hand caressing the women’s faces so as to recall and trace their features. These are powerful works that beyond their inclusion in this show about women, confirm the continuing importance and place of portraiture in regional contemporary practice.

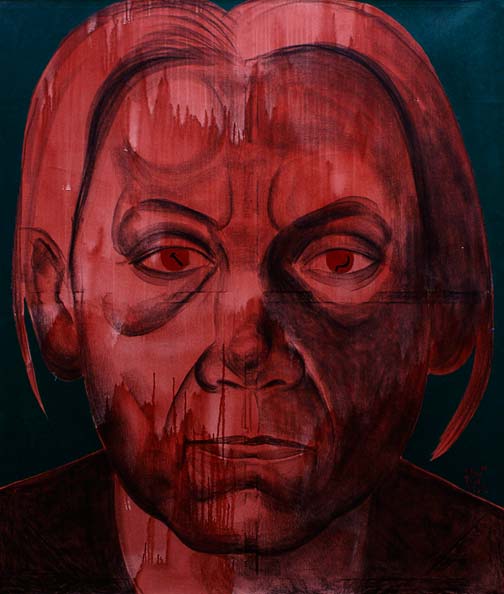

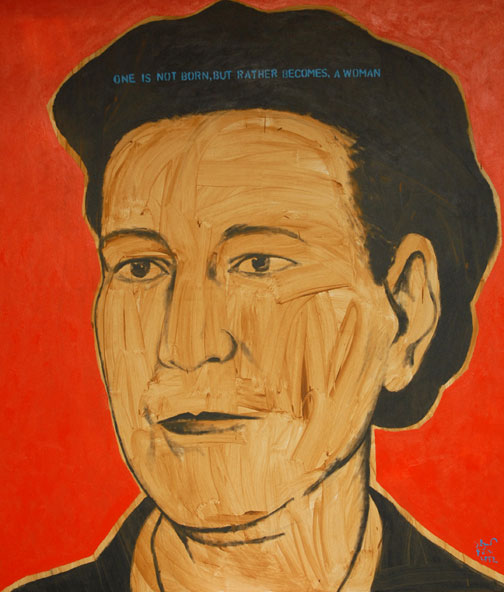

Yet another way of looking at the theme comes to the fore in Vasan’s evocations of iconic women of strength, integrity and intellectual accomplishment hailing from the region and beyond. Amongst others, Burmese democracy movement leader Aung San Suu Kyi, mid 20th century French writer and feminist Simone de Beauvoir, and early 20th century German painter of the poor and disenfranchised, Kathe Kollwitz, find there way into Vasan’s pantheon. Capturing them in a few concise and well-honed brush strokes, the artist succeeds in simultaneously translating these women’s determination and commitment to their causes, as well as their human –as opposed to feminine- vulnerability beneath their respective iconic statures.

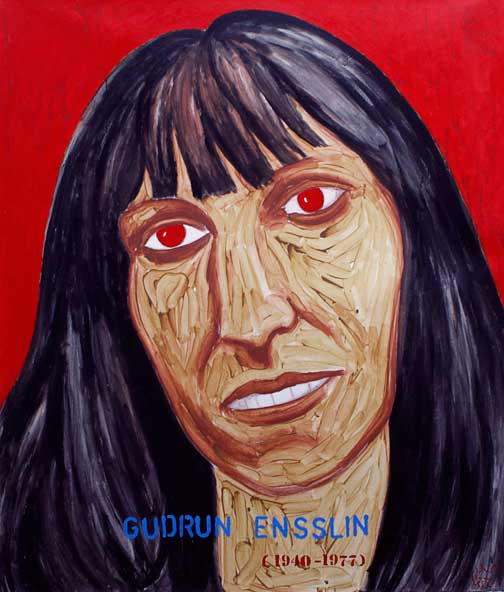

Three more portraits of notorious women, Ulrike Meinhof, Gudrun Ensslin and Phoolan Devi, are also presented.

The first two, infamous rather than famous, depict women guerillas Meinhof and Ensslin. These two, leaders rather than followers, were founding members of West Germany’s anarchic Baader-Meinhof gang or Red Army Faction, active in the early 1970’s. Vasan’s inclusion of this pair may seem surprising but by portraying women guerrillas alongside his own mother and the morally irreproachable Aung San Suu Kyi, the artist revisits a theme grappled with in his 2001 series We come from the same way(7), that of moral choice and the dignity and empowerment that come with one’s ability to determine one’s own fate through a chosen code of conduct, good, bad, or mixed. These paintings may seem deliberately provocative in their inherent glorification of female-induced anarchic violence. Yet seen in the context of this show, the introduction of Meinhof and Ensslin also harks back allusively to woman as active social player of pre-modern times, and thus, to the paradoxically layered identity of submission and defiance of Thailand and wider Southeast Asia’s 21st century woman.

Vasan’s insertion of Phoolan Devi into his line-up of iconic women underscores the artist’s understanding of women’s mixed lot. Devi (1963-2001), otherwise known as the Bandit Queen of India and later a politician, was both a victim of injustice, rape and extreme violence, as well as a murderess who for some years took the law into her own hands as the head of a group of male bandits. Depicted here clutching a riffle, Devi personifies vulnerability turned into strength, and passivity become action. Once again, here as with the previous two women, the artist is less interested in Phoolan Devi’s moral choices than by his anti-hero’s empowerment and transformation. Through intelligence and a profound will to see justice, Devi evolved from subjugated child (she experienced forced marriage at the age of 11), to active woman leader, in control of her own destiny. This portrait, contrary to many of Vasan’s irony-tinged images, is not a caricature. Instead, its stylistic refinement and naturalism emphasizing Vasan’s empathy and absence of judgment for his subject, the canvas captures the subtlety of Devi’s suffering-induced hardness.

Paintings of woman as mother-earth inevitably find their way into Vasan’s Women. A theme of particular interest to the artist and familiar to those who have followed Vasan’s career over the years, here the artist’s earth-mamas are idealized and voluptuous, his four-breasted, moonlit Our Mother bordering on the supernatural, so encapsulating woman as a benign and generous force of nature. Read less literally, with their nearly naïve stylistic idiom and pure colours, Vasan uses these canvases to point elliptically to Thailand and indeed the region’s most ancient animistic traditions which held women to command special powers and a mystique unique to their sex.

Finally, with Miss Universal Vasan explores yet another facet of the complex issue of female identity in contemporary Thailand. Humorous rather than righteously critical, the artist’s playful evocation of the dog-faced urban consumerista, with her keen focus on superficial advertising-sanctioned beauty, hints at a new feminine empowerment that though in this case ill-used, could potentially be unleashed and put to the service of real and lasting female emancipation.

Vasan’s Women is a compact, tightly-edited exhibition. With these new paintings, Vasan Sitthiket uses his versatile expressive language and incisive take on contemporary Thai society to train a sharp eye on the multi-faceted and ever-evolving position of women in Southeast Asian culture. Moving from the specificity and emotional register of his depictions of family women, to the evocation of broader pan-regional issues of wealth and poverty, economic exploitation, and women as simultaneous victims of, and willing participants in, the fraud of consumption-based living, Vasan Sitthiket’s world of women marries form and agenda to forge a positive message of empowerment and change for us all.

Iola Lenzi March 2009

NOTES

(1) Reid, Anthony, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450-1680, vol. I, Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai, 1988, pp. 146-7; 160-1 for a discussion of female independence in many aspects of life in pre-modern Southeast Asia. The author highlights their autonomy in matters ranging from dowrie practices, distinct to repressive Chinese, European and Indian models, to commercial affairs, sexual matters, inheritance and divorce practices. Reid argues that though women had different functions to men, they were not unequal and points out that unlike in China, India and the Middle East, the value of daughters in Southeast Asia was never questioned. Reid also suggests the prevalence of contraception, providing yet further evidence of women’s independence.

(2) Hefner, Robert ed., Market Cultures, Society and Morality in the New Asian Capitalisms, Jennifer Alexander, “Women Traders in the Javanese Marketplaces: Ethnicity, Gender and the Entrepreneurial Spirit”, Westview Press, Oxford, 1998, pp. 211-2 for a discussion of the prominent economic role of women in Javanese trading activities and the Javanese family’s matrifocal structure.

(3) Ibid Reid, p. 81 on the development of male-female distinction in the 17th century. Also, p. 156-7, on the Age of Commerce’s bringing of world religions that conflict in different ways with the existing broad pattern of sexual relations, relative pre marital freedom, monogamy, fidelity within marriage, easy divorce and strong female position in the sexual game. However Reid has reservations, saying that even Islamic shari’a law, stringent in all things relating to women, was interpreted with flexibility in most places beyond the trading cities. For the particular case of Siam, see Rigg, Jonathan, Southeast Asia, Routledge, London, 2003, pp. 257-30 for comments on Buddhism, Confucianism and Islam’s patriarchal tendencies and male domination of political structures in Thailand.

(4) Nathan K.S., Kamali Mohamed Hashim eds., Islam in Southeast Asia-Political, Social and Strategic Challenges for the 21st Century, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 2005, p. 113 for reference (Shamsul A.B.) to the pre-Islamic rituals still permeating the lives of many Malays today.

(5) Barme, S., Woman, Man, Bangkok- Love, Sex, and Popular Culture in Thailand, Silkworm Books, Bangkok, 2006, pp. 4-7 for comments relating to gender in Siamese historiography.

(6) Farmers are farmers, Tadu Gallery, Bangkok, 1998

(7) We come from the same way, Numthong Gallery, Bangkok, 2001